X’s plan to interfere with the election

Elon Musk’s effort to deny Kamala Harris an election victory is already underway. Can it work?

With polls essentially tied and hours to go until Election Day, no one knows for certain who will win the 2024 US presidential election. But we can say with some certainty what will happen if the result is anything other than a landslide victory for Donald Trump: a concerted campaign to delegitimize the election’s results, organized and amplified on Elon Musk’s X.

Today, let’s talk about what we should expect to see in the potentially tumultuous aftermath of the election. While I’m as anxious as anyone else about the result tomorrow, I find it somewhat calming to remember that we already know which narratives and strategies will likely be used to deny Kamala Harris a victory in all but the most convincing of outcomes. When these start to reverberate around the internet tomorrow, there will be at least some comfort to be had in the knowledge that we all saw it coming.

So here’s what to look for, with a focus on where falsehoods about the election will have the greatest intersection with tech platforms.

One: We might not know the results on Election Day. Cognizant of the fact that delayed results breed conspiracy theories, many states have worked over the past four years to speed up the count. The Harris campaign expects same-day results from Georgia, North Carolina, and Michigan, Reuters reported, but Pennsylvania, Arizona and Nevada may take until Wednesday or beyond. The single most effective thing the press could do to calm nerves in the run-up to and immediate aftermath of the election could be to remind their audiences that a multi-day count is normal and not evidence of fraud.

Two: Republicans will claim massive voter fraud again anyway. This is of course a repeat from the 2020 election, when Trump spent the entire year warning that he could only lose if Democrats cast millions of fake ballots for Joe Biden. The Big Lie led to the death and destruction of January 6, but Trump and his enablers doubled down on it. The twist this time is that rather than place the blame on mail-in ballots, which he once feared would favor Democrats, Trump and his campaign surrogate Musk are scapegoating undocumented immigrants.

Musk has posted about the issue more than 1,300 times this year, according to a Bloomberg analysis, and is his most discussed subject online. If the race is tight, expect Musk to continue scapegoating immigrants.

Three: X — and Musk’s X account — will be a central clearinghouse for voter fraud election claims and other election misinformation.

Musk has destroyed most of the financial value of the company once known as Twitter. But it remains the default destination for politics among social networks, and usage of the platform will undoubtedly surge tomorrow.

That gives Musk a potent weapon as he attempts to shape narratives about election results. Having manipulated the platform’s recommendation algorithm to show his posts to more users, he can single-handedly push election narratives to millions of people with the tap of a button. (Over the past day he has become obsessed with the euthanization of a TikTok-famous squirrel at the hands of the state, which he has presented as an example of government overreach.)

Musk and X generally will likely be powerful nodes for what scholars of misinformation call “participatory disinformation”: false and misleading stories shared by average people on social networks that are elevated by influencers to the attention of elites like Musk, who can then turbocharge their distribution. Eventually, the platforms Community Notes feature might offer pushback on false claims — but don’t count on it.

Four: look for “it went viral on X” to be used as a mark of legitimacy and a pressure point on other platforms.

In 2016 and 2020, platforms coordinated to share information about foreign influence operations and other efforts to harm the integrity of their networks. Their policies about which claims would and would not be allowed were fairly similar.

Today, Musk has transformed X into a political operation designed to get Trump elected at all costs. That means not only hosting election misinformation, but actively promoting it. Some of these claims might appear to have gotten millions of views — and this alone will be used to pressure other media outlets into covering the story, and other platforms to continue hosting it or even amplifying it.

Caution may be warranted here. Platformer reported last year that Musk ordered changes to X’s algorithm to ensure that his posts got wider distribution than others. From that moment on, extreme skepticism about X’s public metrics has been warranted.

Five: false claims that get the most traction will be amplified across right-leaning platforms, including Rumble, Substack, and podcasts.

Earlier this year I wrote about the “cinematic universes” that spring up around false and misleading claims, through interconnected series of X posts, newsletters, blogs, Congressional hearings, and other media. (The phony “Haitian immigrants are eating neighborhood pets” is a recent example of this phenomenon.)

While media consumption has been fragmenting and polarizing for decades now, in 2024 we have begun to approach the end state. While large national newspapers and broadcast networks do most of the journalism that the rest of the ecosystem feeds on, voters have never had an easier time creating what researcher Renee DiResta calls “bespoke realities” from their publications and influencers of choice.

Six: mainstream platforms may take a light hand in moderating false and misleading claims.

Meta prohibits misinformation intended to prevent people from voting, but not false claims about the results. In 2020, “Stop the Steal” became one of the fastest-growing Facebook groups in history. The company took that one down. It remains to be seen what the company will do with the inevitable sequel.

Last year, YouTube announced that it would no longer remove false claims about the 2020 election, including claims about widespread voter fraud. Its current policies make no mention of removing false claims of voter fraud in this election, either.

TikTok’s policies make no direct mention of voter fraud, but state that “we label unverified election claims, make them ineligible for recommendation, and prompt people to reconsider before sharing them.”

The only major platform I know that has an explicit ban on phony voter fraud posts is Snap, which prohibits it as part of its policy on content that seeks to delegitimize civic processes: “content aiming to delegitimize democratic institutions on the basis of false or misleading claims about election results, for example.”

As always, the real policy is what you enforce. But most platforms have gone out of their way to let the public know that they are going to take a less active role on election integrity matters than they did last time.

Of course, voter fraud is only one narrative that may come to the fore in the weeks ahead. There are likely still some surprises in store — the results of a foreign influence campaign, or generative artificial intelligence, or some combination of the two.

But whatever dirty tricks are coming, expect X to be at the center of them. Its historical role as the best place to turn to for breaking news means that millions of Americans will be returning there for real-time updates. And its post-2022 incarnation as a right-wing political project means that many of them might not apply the skepticism that is warranted to whatever Musk decides to show them.

In 2016, Mark Zuckerberg called the notion that fake stories on Facebook had influenced the outcome of the election “a pretty crazy idea.” In 2024, Elon Musk appears to have calculated that the idea is so crazy it just might work. As X fills up with fake stories in the days ahead, here’s hoping that the electorate doesn’t fall for it.

More on platform policy and elections: Check out this comprehensive look at current social media companies’ content moderation policies, and recommendations for the period following Election Day. (Jordan Kraemer, Tim Bernard, Diane Chang, Renée DiResta, Justin Hendrix and Gabby Miller / Tech Policy Press)

Governing

- Almost all of the people who have won Elon Musk’s $1 million daily lottery are registered Republicans or appear to lean Republican, this analysis found. (Ben Kamisar, David Ingram, Bruna Horvath and Alexandra Marquez / NBC News)

- Despite Musk promoting it as a lottery, it was not actually a lottery and winners were not chosen by chance, Musk’s lawyers said in court. So you're saying he rigged it? (Chris Palmer and Jeremy Roebuck / Philadelphia Inquirer)

- The giveaway is not illegal and Musk can keep doing it, a judge ruled. (Gary Grumbach, Jane C. Timm, George Solis and Lisa Rubin / NBC News)

- FCC commissioner Brendan Carr threatened to pull NBC’s broadcast license over Harris’ appearance on SNL. Performative nonsense. (Nilay Patel / The Verge)

- A look at how the fringe group behind 2020’s “Stop the Steal” movement has spent years preparing to contest this year’s vote again, this time alongside Elon Musk. (Drew Harwell, Cat Zakrzewski and Naomi Nix / Washington Post)

- Right-wing groups are organizing on Telegram and urging followers to either “stand with the resistance” or accept “tyranny” if Trump doesn’t win. (Paul Mozur, Adam Satariano, Aaron Krolik and Steven Lee Myers / New York Times)

- Elon Musk has become the dominant voice on his platform X in the lead-up to the election. (Kate Conger, Aaron Krolik, Santul Nerkar and Dylan Freedman / New York Times)

- Bluesky, positioning itself as an X alternative, laid out its content moderation plans for Election Day. (Sarah Perez / TechCrunch)

- Meta is extending its block of new election ads past Election Day. (Sara Fischer / Axios)

- A look at the internal conflict inside TikTok over how much politics to allow on the platform. (Emily Baker-White / Forbes)

- Female TikTok users receive more Harris content, while male users receive more Trump content, this experiment found. (Jeremy B. Merrill, Cristiano Lima-Strong and Caitlin Gilbert / Washington Post)

- TikTok users are sharing Trump’s Access Hollywood tape with his comment about grabbing women without consent – a clip that resurfaced in 2016 – as young teens encounter the clips for the first time. (Tatum Hunter / Washington Post)

- A self-described Frenchman, who calls himself Théo, says his intent on betting more than $30 million on Trump winning the election is purely to make money and not to manipulate the outcome. (Alexander Osipovich / Wall Street Journal)

- AI search engine Perplexity announced an elections tracker using data from the Associated Press and Democracy Works. It is unclear whether the companies will be compensated for that data. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- A look at the scientific dispute over Jonathan Haidt’s book about how social media has led to a teen mental health crisis. (Stephanie M. Lee / Chronicle of Higher Education)

- Governments need to start regulating AI in the next eighteen months as the window for risk prevention is closing, Anthropic warns. (Anthropic)

- A look at Microsoft and a16z’s joint recommendations for policy when it comes to AI and startups. (Satya Nadella, Brad Smith, Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz / Microsoft)

- Amazon Web Services’ bid to buy nuclear power for several data centers in Pennsylvania for AI was rejected by US energy regulators. (Anissa Gardizy / The Information)

- Former Twitter CEO Parag Agrawal and other executives can proceed with claims that Musk fired them right as he was closing the takeover deal to avoid paying them severance, a judge ruled. (Malathi Nayak / Bloomberg)

- Grindr illegally imposed a return-to-office policy to force out staff to combat a unionization attempt, the National Labor Relations Board alleged. (Josh Eidelson / Bloomberg)

- The Llama series will be available to US government agencies and contractors for national security uses, Meta said. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- Chinese researchers with ties to the country’s military have reportedly used Meta’s Llama model to develop AI tools for potential military use. (James Pomfret and Jessie Pang / Reuters)

Industry

- OpenAI is reportedly in talks with California’s attorney general office to become a for-profit company. (Shirin Ghaffary and Malathi Nayak / Bloomberg)

- T-Mobile reportedly agreed to pay OpenAI about $100 million over three years to use its technology. (Aaron Holmes / The Information)

- ByteDance reportedly increased its revenue by more than 60 percent, to about $17 billion, in the first half of 2024. (Juro Osawa and Jing Yang / The Information)

- X is officially updating its block feature to allow blocked users to still public posts. (Ivan Mehta / TechCrunch)

- Meta is rolling out a redesign of Horizon OS with its new Quest update, along with a calendar app and the ability to use Travel Mode on a train. (Jay Peters / The Verge)

- Meta’s plans for an AI data center that runs on nuclear power has been reportedly halted because a rare species of bees was discovered on the land marked for the project. (Hannah Murphy and Cristina Criddle / Financial Times)

- Meta plans to use an AI tool, which it calls an “adult classifier,” to catch young Instagram users who lie about their age, director of product management for youth and social impact Allison Hartnett said. (Curtis Heinzl and Kurt Wagner / Bloomberg)

- Ray-Ban parent EssilorLuxottica is betting big on smart glasses as it hit a €100 billion valuation last week. (Silvia Sciorilli Borrelli / Financial Times)

- A Q&A with John Jumper, Google DeepMind’s director who was recently awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry on the future of AI and AlphaFold, an AI model that can predict the structure of proteins. (Richard Nieva / Forbes)

- Amazon, Microsoft, Meta and Google are set to spend a total of more than $200 billion this year to ramp up AI infrastructure. (Mark Bergen and Lynn Doan / Bloomberg)

- Microsoft hired Jay Parikh, former global head of engineering at Facebook, to help ramp up its data center needs as the company tries to match AI’s demand. (Matt Day, Kurt Wagner and Dina Bass / Bloomberg)

- A profile of Amy Hood, Microsoft’s longtime chief financial officer overseeing the company’s billions of dollars in spending in AI. (Tom Dotan / Wall Street Journal)

- Apple is showing more ChatGPT integration with Siri in the second beta of iOS 18.2. There will apparently be a limit on free usage. (Juli Clover / MacRumors)

- Apple is acquiring photo editing company Pixelmator. (Chance Miller / 9to5Mac)

- Anthropic is upping its price for Claude 3.5 Haiku, which it previously said would cost the same as Claude 3 Haiku. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- Big tech companies saw strong growth in advertising products last quarter as consumer spending, generative AI, and political ads ramped up. (Sara Fischer / Axios)

- A week-long experiment where generative AI took over all decisions in this author’s life. (Kashmir Hill / New York Times)

- The case of Rita Murad, an Arab Israeli college student who went to prison for posting viral images on her Instagram stories the morning of Oct. 7. (Jesse Barron / New York Times)

- A look at AI’s potential in Hollywood, visual effects and film, as others in the industry rebuke the use. (Devin Gordon / New York Times)

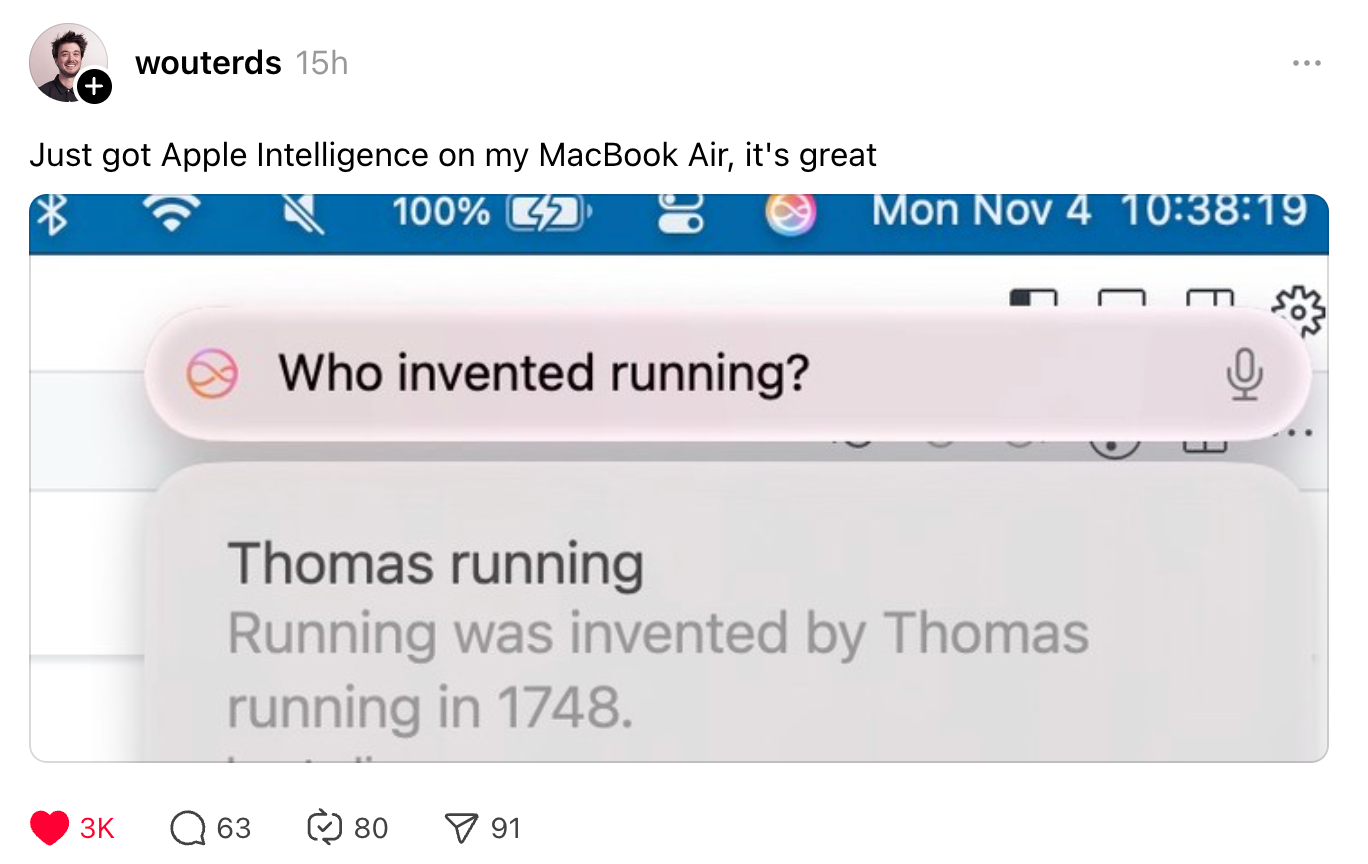

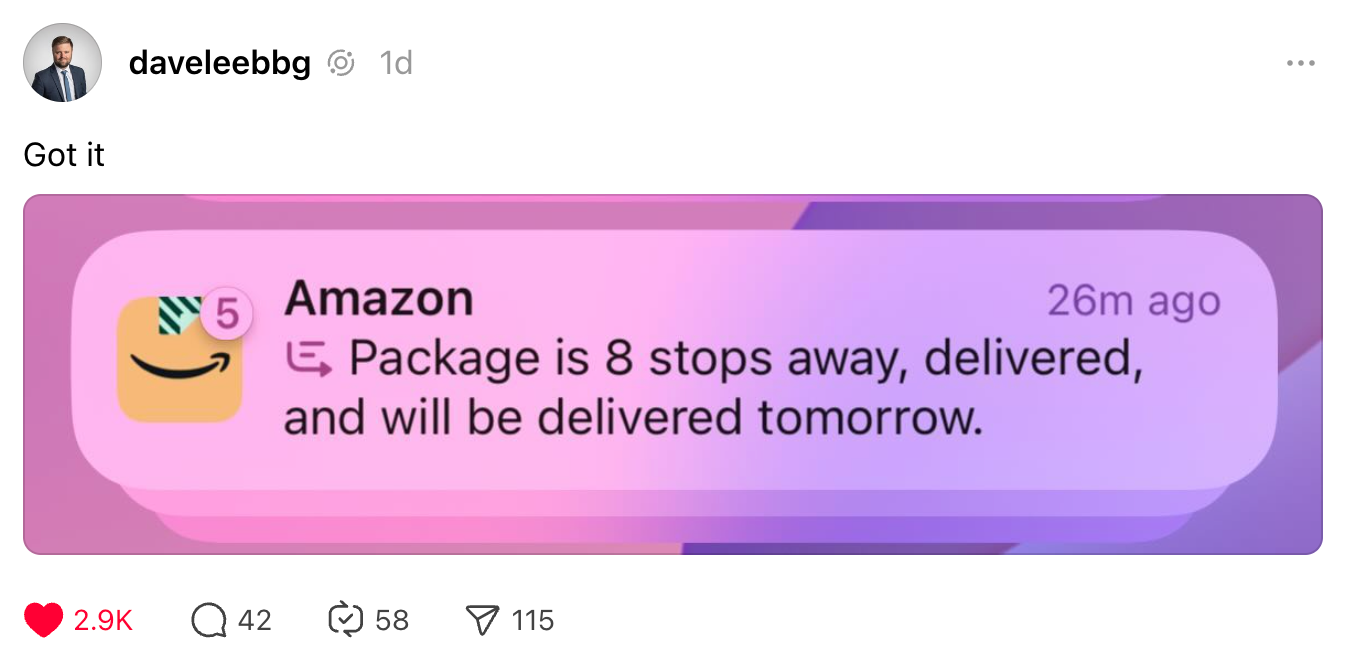

Those good posts

For more good posts every day, follow Casey’s Instagram stories.

(Link)

(Link)

(Link)

Talk to us

Send us tips, comments, questions, and election results: casey@platformer.news.