Can AI regulation survive the First Amendment?

California’s first effort to regulate AI slop hit a wall. What now?

I.

In recent decades, government efforts to regulate the tech industry have lagged significantly behind the growth of new technologies. But the rise of artificial intelligence, which has coincided with AI developers loudly warning that their products carry significant risks of harm, has prompted lawmakers to work more quickly than usual.

Nowhere has this been more true than in California.

The state where Google, OpenAI, Anthropic and others are headquartered has been in the news this week for an bill that did not become law: Senate Bill 1047, which would have required safety testing for large language models that cost more than $100 million to train and created legal liabilities for harms that emerge from those models.

The bill drew strong opposition from most of the big AI companies, along with a host of venture capitalists and other industry players. And while the bill that reached his desk was heavily watered down from earlier versions, on Sunday, Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed the bill. (Newsom said he vetoed it not because it was too strong but because it was too weak, though as far as I can tell almost no one thinks he actually believes this.)

My inbox filled up this week with messages from the bill’s advocates, who accused Newsom of being reckless and exposing Californians to all manner of harms. But I suspect Newsom would sign another version of this bill, perhaps as early as next year — particularly if the next generation of models meaningfully increase the risk of all the harms that this year’s bill attempted to mitigate that.

I say that because, despite vetoing SB 1047, Newsom signed 18 other AI regulations into law. Taken together, it may be the most sweeping package of legislation we have seen so far intended to regulate the misuses of generative AI.

The laws, some of which don’t take effect until 2026, include:

- Extending a ban on child sexual abuse materials to include CSAM created or altered by generative AI.

- Making it illegal to blackmail someone with AI-generated, non-consensual nude images of them.

- Requiring platforms to create channels for users to report deepfake nudes that resemble them. Platforms are required to block the distribution of those images while they investigate and remove them if the reports are substantiated.

- Requiring that AI models add digital watermarks to their output disclosing their provenance.

- Requiring studios to get actors’ permission before using digital likenesses of them, and extending those protections to performers after they die.

- A requirement that AI developers reveal the sources of their training data and publish it on their website. They must also say whether copyrighted or licensed data is included.

- A requirement that healthcare providers disclose when they use generative AI to communicate with patients, and requires physicians to supervise the use of AI in their practices.

Newsom also announced an initiative to build further guardrails around the use of AI that will be led by Fei-Fei Lee, an AI pioneer and startup founder, along with an AI ethicist and a dean at the University of California at Berkeley.

These bills take important steps to address harms taking place right now — not just in California, but all over the world. But in some cases, they address those harms by restricting free expression — and it’s here that the state may soon find that it has overstepped.

II.

California’s newly signed laws also seek to restrict the use of AI in ways that could deceive voters during an election. One law requires political advertisers to disclose the use of generative AI in their ads. Another requires social platforms to remove or label deepfakes related to the election, as well as to create a channel for users to report such deepfakes to the platform. And a third would punish anyone who distributes deepfakes or other disinformation intended to deceive voters within 60 days of an election.

On Wednesday, though, a federal judge blocked that third law — Assembly Bill 2839 — from taking effect. Here’s Maxwell Zeff at TechCrunch:

Shortly after signing AB 2839, Newsom suggested it could be used to force Elon Musk to take down an AI deepfake of Vice President Kamala Harris he had reposted (sparking a petty online battle between the two). However, a California judge just ruled the state can’t force people to take down election deepfakes – not yet, at least. [...]

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the original poster of that AI deepfake – an X user named Christopher Kohls – filed a lawsuit to block California’s new law as unconstitutional just a day after it was signed. Kohls’ lawyer wrote in a complaint that the deepfake of Kamala Harris is satire that should be protected by the First Amendment.

US District Judge John Mendez agreed, ordering a preliminary injunction ordering that the law not take effect — except for a plank of the bill that requires audio-only deepfakes to carry disclosures. (Which the plaintiff did not challenge.)

Supreme Court precedent illuminates that while a well-founded fear of a digitally manipulated media landscape may be justified, this fear does not give legislators unbridled license to bulldoze over the longstanding tradition of critique, parody, and satire protected by the First Amendment. YouTube videos, Facebook posts, and X tweets are the newspaper advertisements and political cartoons of today, and the First Amendment protects an individual’s right to speak regardless of the new medium these critiques may take. Other statutory causes of action such as privacy torts, copyright infringement, or defamation already provide recourse to public figures or private individuals whose reputations may be afflicted by artificially altered depictions peddled by satirists or opportunists on the internet…

The record demonstrates that the State of California has a strong interest in preserving election integrity and addressing artificially manipulated content. However, California’s interest and the hardship the State faces are minimal when measured against the gravity of First Amendment values at stake and the ongoing constitutional violations that Plaintiff and other similarly situated content creators experience while having their speech chilled.“

I’m sympathetic to the judge’s argument here. The “deepfake” at issue strikes me as obvious satire. And the First Amendment should apply even in cases where the satire is less apparent.

But as Rick Hasen writes at Election Law Blog, there may have been a path forward to allow such content on social networks so long as it is labeled as being AI-generated.

“The judge’s opinion here lacks nuance and recognition that a state mandatory labeling law for all AI-generated election content could well be constitutional,” writes Hasen, a law professor at UCLA. “I fear that the judge’s meat-cleaver-rather-than-scalpel-approach, if upheld on appeal, will do some serious harm to laws that properly balance our need for fair elections with our need for robust free speech protection.”

Perhaps an appeals court will find more nuance here. But the past half-decade or so of state-level tech regulation has repeatedly walked into the same buzzsaw. Lawmakers accuse social platforms of causing harm, and pass laws seeking to blunt those harms — only to be told time and time again by judges that their laws are unconstitutional. It happens with efforts to ban TikTok; it happens with efforts to force visitors to porn websites to verify their age; it happens with efforts to regulate social networks’ recommendation algorithms.

Everyone has an interest in elections taking place in an environment where voters can easily tell fact from fiction. We also have an interest in being able to easily remove malicious deepfakes of ourselves from social platforms, or otherwise prevent our digital likenesses from being used in harmful ways.

In the coming year, I expect many states to follow California’s lead, and seek to pass similar legislation that prevents these obvious AI harms from continuing to occur. When they do, though, they may learn the same lesson California just did — that some of the most obvious ways to protect people from AI may not be constitutional.

On the podcast this week: Kevin and I talk through California's new AI regulations. Then, The Information's Julia Black joins to talk about Silicon Valley's growing fascination with fertility tech — and baby-making in general. And finally, some fun updates on OpenAI, Reddit, and Sonos.

Apple | Spotify | Stitcher | Amazon | Google | YouTube

Governing

- WP Engine sued Automattic and WordPress co-founder Matt Mullenweg, accusing them of extortion and abuse of power. (Ivan Mehta / TechCrunch)

- For a smart look at the likely motivations of all the players in this increasingly messy fight, I recommend Gergely Orsoz’s measured view at Pragmatic Engineer.

- WordPress parent Automattic had asked hosting service WP Engine for an eight percent cut of its revenue per month before its public trademark dispute. (Emma Roth / The Verge)

- Biden signed a new law limiting certain federal environmental reviews and permitting requirements for some semiconductor chip projects. (Lindsey Choo / Forbes)

- A study published Wednesday in Nature found conservatives share more falsehoods and low-quality information online than liberals — even when you let conservatives designate what information is false and low quality. (Will Oremus / Washington Post)

- The Oversight Board announced it would hear a case related to the removal of content regarding an assassinated political candidate running for office in Mexico. From the description, it sounds like a clear case of overreach by Meta. (Oversight Board)

- Harvard students connected Meta’s Ray-Ban smart glasses to facial recognition service PimEyes in a demonstration of how easy it already is to pull up the personal information of anyone in view. (Joseph Cox / 404)

- Telegram CEO Pavel Durov said that recent coverage of the company’s increased responsiveness was overstated, and that little had changed. It’s almost like he wants to return to French prison. (Jake Rudnitsky / Bloomberg)

- An interview with Irina Bolgar, Durov’s former romantic partner of 10 years, who has accused him of abusing the youngest of the three children they had together. (Adam Satariano and Paul Mozur / New York Times)

- Elon Musk’s political giving to Republicans began earlier than previously reported, with the billionaire donating tens of millions of dollars to right-wing causes starting in 2022. (Dana Mattioli, Joe Palazzolo and Khadeeja Safdar / Wall Street Journal)

- The use of facial recognition technology among police is surging in London. Police used it 117 times from January to August, up from 32 times in the three years between 2020 and 2023. (Yasemin Craggs Mersinoglu / Financial Times)

- South Korea is seeing a deluge of deepfake nudes of women, which have deeply traumatized victims. Parliament passed a law to make possessing or watching deepfake porn illegal. (Hyung-Jin Kim / AP)

- Meta is teaming up with UK banks in a “threat intelligence sharing program” in an effort to stop scammers. (Akila Quinio / Financial Times)

- The Philippines is imposing a 12 percent value-added tax on digital service providers including Netflix, HBO and Disney. (Andreo Calonzo / Bloomberg)

Industry

- OpenAI raised $6.6 billion in a funding round at a $150 valuation led by Thrive Capital. Microsoft added $750 million to its existing $13 billion investment. (Shirin Ghaffary, Katie Roof, Rachel Metz and Dina Bass / Bloomberg)

- The valuation makes OpenAI more valuable on paper than any venture-backed startup at the time of its IPO. (Rosie Bradbury / Pitchbook)

- OpenAI’s mega funding round includes a $4 billion revolving credit line. (Hayden Field / CNBC)

- It also reportedly asked investors to avoid backing rival startups like xAI and Anthropic. I’m old enough to remember when its nonprofit board said the company would shut down and go help a rival if the rival got closer to building a superintelligence. (George Hammond and Stephen Morris / Financial Times)

- A look at recent turmoil at OpenAI suggests that burnout and exhaustion have been a factor in executives’ departures. (Rachel Metz / Bloomberg)

- OpenAI announced Canvas, a way of using ChatGPT that opens a side-by-side window for easier usage. It’s a clone of Anthropic’s Artifacts feature. (Maxwell Zeff / TechCrunch)

- A look at Threads’ integration into the fediverse and Meta’s strategy to move towards a more open internet. (Will Oremus / Washington Post)

- Google DeepMind and BioNTech are building AI lab assistants to help plan experiments and predict their outcomes. (Madhumita Murgia and Ian Johnston / Financial Times)

- Several teams at Google are reportedly working on AI reasoning software similar to OpenAI’s o1 model. (Julia Love and Rachel Metz / Bloomberg)

- You can now use Google Lens to ask questions about the video you are taking from your smartphone. (Emma Roth / The Verge)

- Google’s AI-powered search results now have ads. Which is great news for my burgeoning edible rocks business. (Emma Roth / The Verge)

- Google Gemini’s voice mode is adding new languages in the coming weeks, including French, German, Portuguese, Hindi, and Spanish. (Alison Johnson / The Verge)

- YouTube extended the length of Shorts to three minutes and added new templates and a trending Shorts page to its mobile app. (Sarah Perez / TechCrunch)

- The Gmail app is getting redesigned summary cards that are more dynamic. (Abner Li / 9to5Google)

- Third-party YouTube app for the Apple Vision Pro, Juno, was removed from the app store. The app violated YouTube guidelines, Google warned. (Emma Roth / The Verge)

- Apple’s new “contact sync” tweak could stifle growth for new social apps, developers worry. A classic privacy versus competition trade-off. (Kevin Roose / New York Times)

- Elon Musk rambled for a while during an appearance at a recruiting event for xAI. (Kylie Robison / The Verge)

- A standalone Microsoft Office 2024 is now available for Mac and PC users. (Tom Warren / The Verge)

- Amazon is set to roll out more ads in movies and shows on Prime Video in its push further into ad-supported streaming services. (Daniel Thomas / Financial Times)

- Amazon’s new Fire HD 8 tablet line has an upgraded RAM, a reported 50 percent step up from the previous model. (Ryan McNeal / Android Authority)

- Character.ai is pivoting to focus on improving its chatbots instead of AI models as it gets outspent by competitors, interim CEO Dominic Perella said. (Cristina Criddle / Financial Times)

- Twitch made it easier for streamers to become partners eligible for ad revenue by counting raids toward a streamer’s number of concurrent viewers. They need to average 75 concurrents across a certain amount of watch time to quality. (James Hale / TubeFilter)

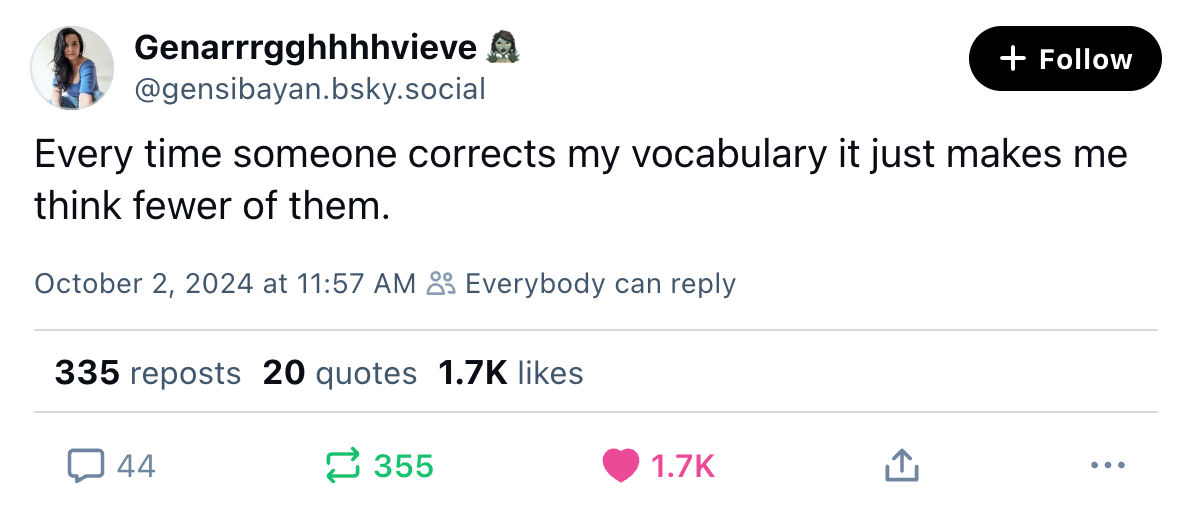

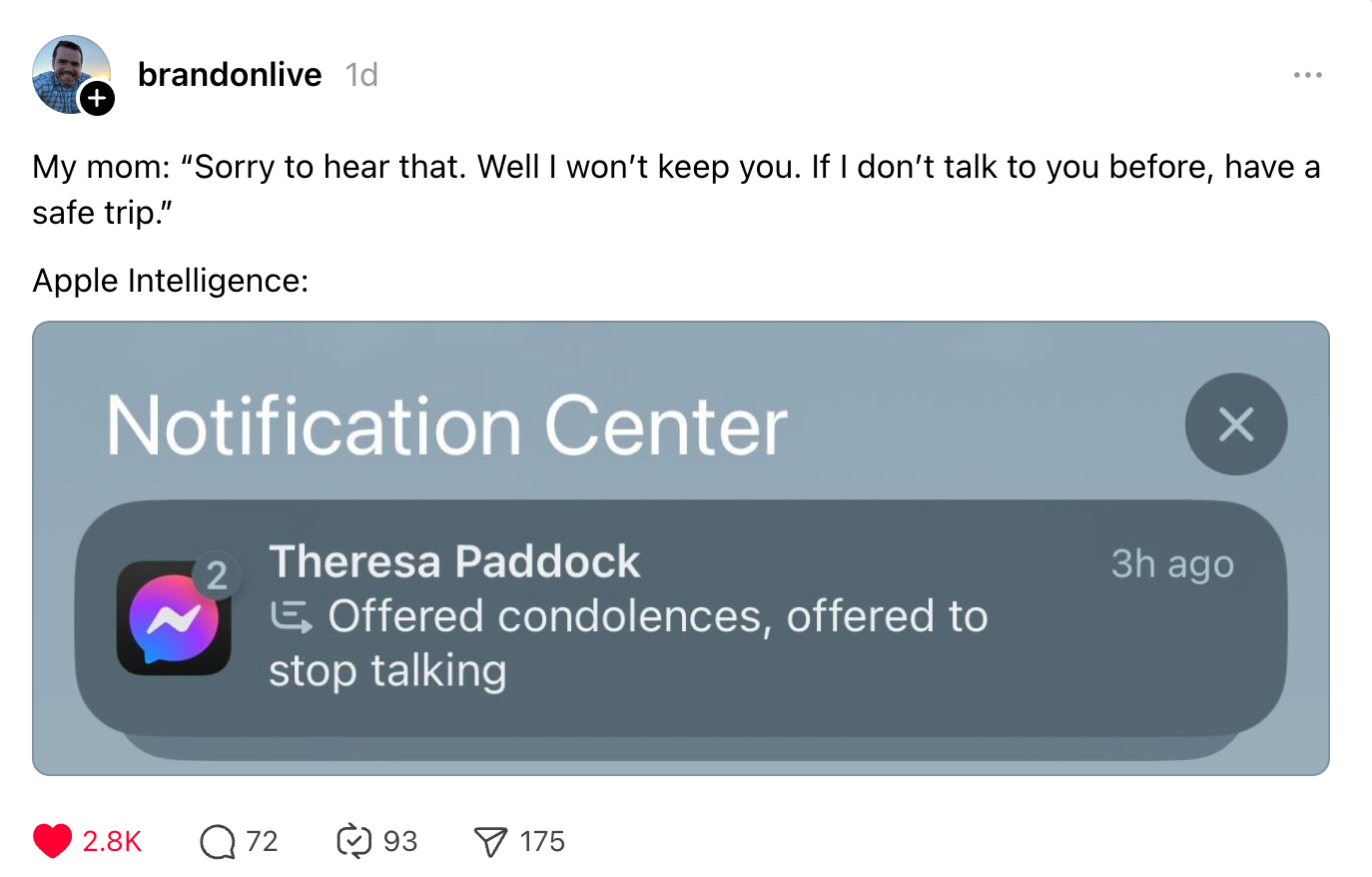

Those good posts

For more good posts every day, follow Casey’s Instagram stories.

(Link)

(Link)

(Link)

Talk to us

Send us tips, comments, questions, and constitutional AI regulations: casey@platformer.news.