OpenAI launches its agent

Hands on with Operator — a promising but frustrating new frontier for artificial intelligence

This is a column about AI. My boyfriend works at Anthropic. See my full ethics disclosure here.

For the past few months, the big artificial intelligence labs have signaled that 2025 will be a breakout year for agents: tools that use computers on your behalf, working across different apps to perform multi-step operations just like humans do.

Agents have rapidly become a top priority at AI labs, as they represent a key milestone on the way toward building full-featured virtual coworkers. Starting last year, a steady drip of announcements signaled that researchers are rapidly making progress toward that goal.

Anthropic introduced its first take on agents, which it calls “computer use,” into its API in October. Two months later, Google said that its Gemini 2.0 models were designed for “the agentic era.”

Despite those announcements, though, until now most agents have only been available to developers. As of this week, though, that’s starting to change.

On Wednesday, Google announced that the mobile version of Gemini can now carry out tasks across different apps, such as searching for upcoming sports games and creating calendar entries for them, with a single prompt. A day later, the upstart AI company Perplexity announced a similar agent for its Android app.

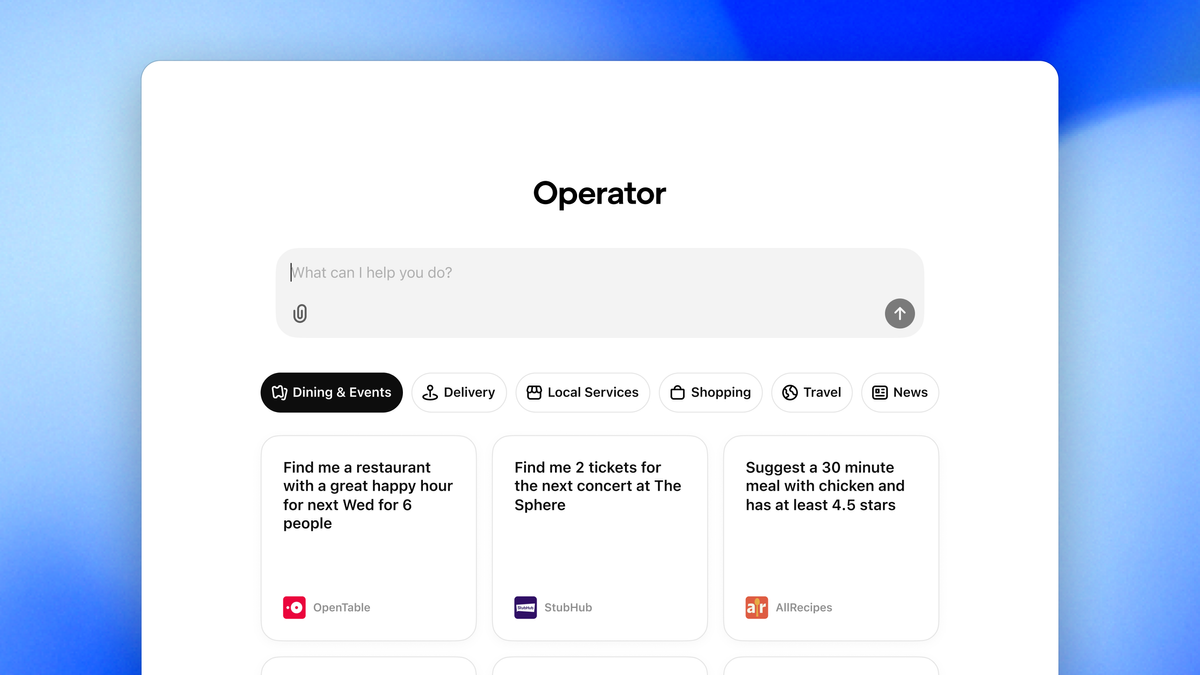

And in the most ambitious AI agent launch to date, on Thursday OpenAI announced Operator: an AI agent that can browse the web and take actions on your behalf. In a live demo on Thursday morning, CEO Sam Altman and three of his coworkers showed some of what Operator can do: shop for groceries on Instacart, hunt for concert tickets on Stubhub, and booking a reservation at a local restaurant through OpenTable.

Operator is available through what OpenAI is calling a “research preview,” and is currently available only to users of the $200-a-month ChatGPT Pro tier. The company plans to release it to users of its $20-a-month Plus plan and other users in the months ahead, it said. For developers, it will be available in the company’s API within a few weeks, the company said.

OpenAI explained how Operator works in a blog post:

Operator is powered by a new model called Computer-Using Agent (CUA). Combining GPT-4o's vision capabilities with advanced reasoning through reinforcement learning, CUA is trained to interact with graphical user interfaces (GUIs)—the buttons, menus, and text fields people see on a screen.

Operator can “see” (through screenshots) and “interact” (using all the actions a mouse and keyboard allow) with a browser, enabling it to take action on the web without requiring custom API integrations.

If it encounters challenges or makes mistakes, Operator can leverage its reasoning capabilities to self-correct. When it gets stuck and needs assistance, it simply hands control back to the user, ensuring a smooth and collaborative experience.

After OpenAI’s demo, I paid to upgrade my ChatGPT subscription so I could use Operator. A few hours later, it was enabled on my account, and I spent the afternoon trying various prompts to get a sense of what it can do.

How you feel about Operator will depend heavily on what you hope to get out of it. If you’re looking for a polished virtual assistant to which you can confidently hand off shopping and research tasks, I suspect you’ll be disappointed: at the moment, using Operator is significantly slower, more frustrating, and more expensive than simply doing any of these tasks yourself.

If you’re interested in the bleeding edge of AI progress, though, and want to get a sense of what the future could look like, Operator offers a compelling demonstration. Using it on Thursday reminded me a bit of the first time I took a ride in one of Google’s self-driving cars: half-baked though the product may have been at the time, it also represented an extraordinary technological achievement and seemed likely to shape our world for years to come.

Of all the tasks I gave to Operator, the one it performed best was probably the simplest. (It was also a task that Operator suggested I try in a grid of suggested prompts under the chatbot interface.) The task was to “suggest some top-rated walking tours I can sign up for in London.” Once I hit “go,” Operator opened TripAdvisor in a browser, did a search, and presented me with a series of walking tours to consider with the relevant links. The whole thing only took about a minute, and I could have easily left the browser tab to do something else while it worked.

Of course, there’s nothing that impressive about generating a list of London walking tours: there are many such lists all over the web, and the free version of ChatGPT will also give you a good list even faster than Operator. But there’s still something striking about telling a computer to do something and then watch it open a browser tab, type queries, click on buttons and present you with a report.

Operator also performed decently well on a task that I borrowed from Ethan Mollick, an associate professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, who had used it to test Anthropic’s agent: “put together a lesson plan on the Great Gatsby for high school students, breaking it into readable chunks and then creating assignments and connections tied to the Common Core learning standard.”

Operator took about eight minutes to complete the task, but when it finished it presented me with a curriculum that seemed to satisfy all the requirements. As with the TripAdviser example, though, I found that the free version of ChatGPT answered it just as well — and did so more quickly.

For the moment, then, if your question is “what can Operator do better than existing tools?” the answer is not clear. It can take action on your behalf in ways that are new to AI systems — but at the moment it requires a lot of hand-holding, and may cause you to throw up your hands in frustration.

My most frustrating experience with Operator was my first one: trying to order groceries. “Help me buy groceries on Instacart,” I said, expecting it to ask me some basic questions. Where do I live? What store do I usually buy groceries from? What kinds of groceries do I want?

It didn’t ask me any of that. Instead, Operator opened Instacart in the browser tab and begin searching for milk in grocery stores located in Des Moines, Iowa.

At that point, I told Operator to buy groceries from my local grocery store in San Francisco. Operator then tried to enter my local grocery store’s address as my delivery address.

After a surreal exchange in which I tried to explain how to use a computer to a computer, Operator asked for help. “It seems the location is still set to Des Moines, and I wasn't able to access the store,” it told me. “Do you have any specific suggestions or preferences for setting the location to San Francisco to find the store?”

At that point, I asked to take over. Operator handed me the reins, and I logged into my account and picked my usual grocery store. From there, I was able to add a few items into my cart by asking for them specifically. The process was painstaking and inefficient in a way that personally made me laugh but I imagine might drive others insane. In the end, adding six bananas, a 12-pack of seltzer, and a package of raspberries to a cart had taken me 15 minutes.

The experience revealed to me one of Operator’s key deficiencies: it can use a web browser, but it cannot use your web browser. This matters a lot, because your browser is already set up for you to use the web efficiently. You’re already logged in to the services you use most, and many of those services are further modified to reflect your personal preferences and make using them more efficient. Open a browser on a different computer, and every single time you’re starting from scratch.

I felt this pain again when I tried another of Operator’s suggestions — checking the current price of an UberX to the airport. Operator successfully pulled up Uber’s website, but found that to check the price I would need to log in. This led to a tedious back-and-forth where I gave Operator first my email address, then my phone number, and then a code that Uber sent me over SMS — and watched Operator go dutifully re-type that information into its browser. Getting the price of an Uber ultimately took five minutes — which is four minutes and 50 seconds longer than it takes me to check the price of an Uber on my phone.

Using its own browser has privacy and security benefits for Operator users: the app doesn’t store your passwords or credit card information or other data that could easily be misused. But this also has a lot of drawbacks — Dan Shipper, who has been testing Operator for a few days, found that it often cannot access websites because they have blocked OpenAI from crawling it. So if your dreams of using Operator involve doing things with YouTube, or Reddit, or Figma, you’ll find yourself out of luck.

Ultimately, I think of this first version of Operator as a set of capabilities that are necessary but not sufficient to create a true AI agent. If any of this is to work, it first has to be turned into an actual product. No designer would make an online grocery service that didn’t start by asking the customer where he lives, or that made you log in to your account every single time you visited. But that’s how Operator works today.

It’s important to be honest about the limitations of these systems today. But it’s often more illuminating to examine the rate of change. In October, Anthropic’s agent scored 14.9 percent on OSWorld, an evaluation to test agents. Today, just three months later, OpenAI said that its CUA model scored 38.1 percent on the same evaluation. And humans, for what it’s worth, only score 72.4 percent.

Agents have a long way to go in product quality before they’re truly useful to the average person. But if the rate of change holds steady, that long way to go might not take as long as you think.

OpenAI and Stargate

- Sam Altman and Elon Musk are arguing on X after Stargate, OpenAI’s infrastructure project, announced that it would spend $500 billion on AI data centers and Musk claimed Stargate didn’t have the money. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- OpenAI and SoftBank will reportedly each invest about $19 billion in the joint venture. (Natasha Mascarenhas and Amir Efrati / The Information)

- Stargate reflects OpenAI's shift away from its reliance on Microsoft after it came to feel like Microsoft wasn't giving it enough computing resources. (Tom Dotan and Deepa Seetharaman / Wall Street Journal)

- But Microsoft will still likely benefit from the arrangement anyway. (Dina Bass / Bloomberg)

Elsewhere in OpenAI:

- ChatGPT experienced a major outage on Thursday morning, affecting both the consumer product and the API. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- Sam Altman held a lengthy phone call with President Trump last week positioning the AI race as a competition with China. (Kate Rooney / CNBC)

- OpenAI spent $1.76 million on lobbying last year, up 700 percent from the year before. (James O'Donnell / MIT Technology Review)

- The company told an Indian court that it can’t delete old training data from ChatGPT, saying it has legal obligations to preserve the data related to lawsuits in the United States. (Arpan Chaturvedi, Aditya Kalra and Munsif Vengattil / Reuters)

On the podcast this week: Kevin and I recount TikTok's return from the dead. Then, we discuss the rise of Trump family memecoins. And finally, MSNBC's Chris Hayes joins us to discuss his new book on attention.

Apple | Spotify | Stitcher | Amazon | Google | YouTube

Governing

- Trump signed an executive order order that artificial intelligence be developed "free from ideological bias." Good luck with that, everyone. (Matt O'Brien and Sarah Parvini / AP)

- ByteDance is considering alternatives to selling TikTok in the US, said board member Bill Ford, including the option of transferring local control. (Jack Sidders, Lisa Ambramowicz and Jonathan Ferro / Bloomberg)

- Trump questioned the national security risk posed by TikTok, asking if it was “that important for China to be spying on young people.” He said smartphone hardware pose a larger risk. (Justin Sink / Bloomberg)

- TikTok users say the app doesn’t feel the same after its brief shutdown, as some express concern over the multiple references thanking Trump. (Tatum Hunter, Lisa Bonos, Gaya Gupta and Heather Kelly / Washington Post)

- The Trump administration terminated the Cyber Safety Review Board that was investigating Salt Typhoon, the China-linked hacking group that breached nine telecommunications networks. (Becky Bracken / Dark Reading)

- Trump signed an executive order to establish a cryptocurrency working group that will advise on digital asset policy and condiser creating a bitcoin reserve. SIGH. (Hannah Lang and Trevor Hunnicutt / Reuters)

- More than 50 popular subreddits, including r/formula1 and r/military, banned links to X after Musk made what looked like a Nazi salute at a rally after Donald Trump’s inauguration. X is dying all the time for all sorts of reasons, but this one will hurt the company more than most — if it lasts. (Mia Sato / The Verge)

- An in-depth visual analysis of how nine prominent podcasters positioned themselves as the main source of information for millions of young men and rallied them for Trump. (Davey Alba, Leon Yin, Julia Love, Ashley Carman, Priyanjana Bengani, Rachael Dottle and Elena Mejia / Bloomberg)

- A look at how the revamped DOGE structure gives Elon Musk more power, as Vivek Ramaswamy departs the commission amid reported tension between the billionaires. (Faiz Siddiqui, Elizabeth Dwoskin and Jeff Stein / Washington Post)

- Google restored Joe Biden to search results for US presidents, blaming a “data error” for the temporary omission. (Jennifer Elias / CNBC)

- Your questions on why you might find yourself suddenly following Trump or JD Vance on Meta platforms, answered. I've gotten lots of reader questions about this one — give it a read if you're one of these folks. (Mike Isaac / New York Times)

- About 45 percent of Meta employees oppose its termination of DEI programs, according to a Blind survey, while 43 percent agreed. (Jae Bae / Blind Workplace Insights)

- AI startup Scale AI faces a third lawsuit over alleged labor practices in over a month. Workers claimed they had psychological trauma from reviewing disturbing content without proper safeguards. (Charles Rollet / TechCrunch)

- A federal court ruled that warrantless “back door” searches under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act are unconstitutional. (Patrick G. Eddington / CATO Institute)

- An interview with Pinterest CEO Bill Ready on why the company is backing laws aimed at restricting cell phone use in classrooms. Could it be because most of his users are older than 40 and this costs him nothing??? (Naomi Nix / Washington Post)

- The UK’s antitrust regulator opened dual probes into Apple and Google’s mobile ecosystems to assess whether they violate competition rules. (Ryan Browne / CNBC)

- Google reportedly provided Israel’s military with access to the company’s AI technology from the initial weeks of the war in Gaza, according to internal documents. (Gerrit De Vynck / Washington Post)

- India lifted its restrictions banning WhatsApp from sharing user data with Meta. (Manish Singh / TechCrunch)

Industry

- ByteDance reportedly plans to spend more than $12 billion on AI infrastructure this year, with $5.5 billion slated for buying AI chips in China. (Zijing Wu and Eleanor Olcott / Financial Times)

- ByteDance released Doubao-1.5-pro, a new version of its flagship AI model, which it says outperforms OpenAI’s o1 in a benchmark measuring AI models’ ability to understand and respond to complex instructions. (Liam Mo and Brenda Goh / Reuters)

- A look at the numerous design tweaks, advertisements and feature rollouts Meta made to Instagram and Facebook in the days before TikTok shut down. (Louise Matsakis / Wired)

- An interview with intellectual property lawyer Mark Lemley on AI copyright and why he decided to quit representing Meta. (Kate Knibbs / Wired)

- Threads is getting some new features, including a tool to schedule posts and the ability to view more metrics in Insights. (Sarah Perez / TechCrunch)

- Anthropic announced a new feature, Citations that lets developers add source documents for answers from Claude, to reduce errors. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- Google is reportedly making another investment of more than $1 billion into Anthropic. (George Hammond, Madhumita Murgia and Arash Massoudi / Financial Times)

- Google debuted a range of ChromeOS features focused on accessibility, including the ability to control the computer with facial expressions. (Antonio G. Di Benedetto / The Verge)

- Google’s AI Overviews in Circle to Search is being expanded to more visual searches and will have new one-tap actions. (Mishaal Rahman / Android Faithful)

- The new Samsung Galaxy S25 will have support for the latest multimodal Gemini Nano model. (Mishaal Rahman / Android Police)

- Visible URLs in Google’s mobile search results will now only show the domain instead of including “breadcrumbs.” (Umar Shakir / The Verge)

- YouTube is adding new experimental features for Premium users, including high-quality audio and a faster playback speed option on mobile. (Ivan Mehta / TechCrunch)

- The New England Patriots shut down their team's Bluesky account after the NFL told them Bluesky “is not an approved social media platform” yet. It should be! For one thing, Bluesky links are still allowed on most of Reddit! (Wes Davis / The Verge)

- Microsoft signed a deal to buy 3.5 million carbon credits worth hundreds of millions of dollars over 25 years from Brazilian startup Re.green to help restore part of the Amazon and Atlantic forests. (Kenza Bryan / Financial Times)

- Tumblr launched Tumblr TV, a GIF-finding feature, as a new tab in its app, now including video content. (Wes Davis / The Verge)

- A profile of Chinese AI lab DeepSeek and its new DeepSeek-V3 model, which it says can compete with other major chatbots but only uses 2,000 Nvidia chips costing $6 million. (Cade Metz and Meaghan Tobin / New York Times)

- Hugging Face released SmolVLM-256M and SmolVLM-500M, which it says are the smallest AI models that can analyze images, short videos and text. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- Substack launched its Creator Accelerator fund, a $20 million program to recruit popular creators from other platforms. The main promise is that for approved creators, Substack will guarantee that anyone who moves from TikTok, Patreon, or other rivals will make at least as much on Substack as they did on their previous platform for one year. (Lauren Forristal / TechCrunch)

- Consumers spent almost $1.1 billion on AI apps including ChatGPT and Gemini last year, a 200 percent increase over the year prior. (Sarah Perez / TechCrunch)

- A look at a new test, “Humanity’s Last Exam,” which challenges AI systems with about 3,000 difficult-to-answer questions. (Kevin Roose / New York Times)

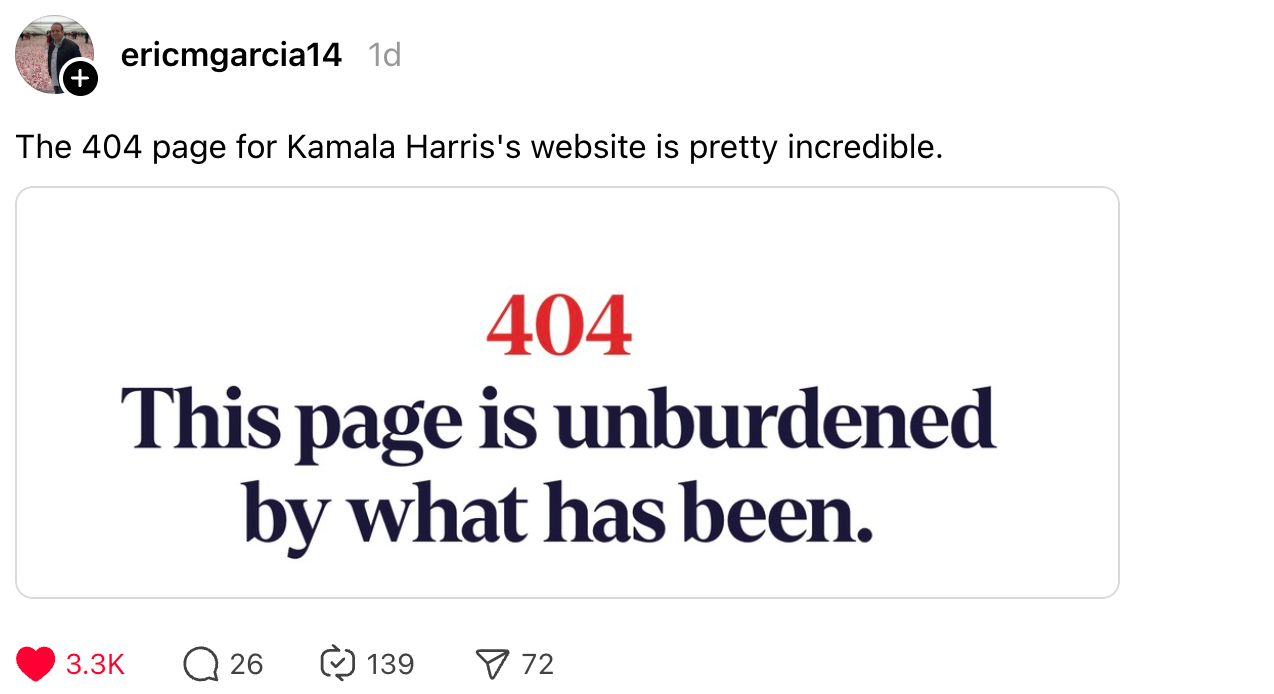

Those good posts

For more good posts every day, follow Casey’s Instagram stories.

(Link)

(Link)

(Link)

Talk to us

Send us tips, comments, questions, and Operator homework: casey@platformer.news. Read our ethics policy here.