How chatbots could spark the next big mental health crisis

New research from OpenAI shows that heavy chatbot usage is correlated with loneliness and reduced socialization. Will AI companies learn from social networks' mistakes?

This is a column about AI. My boyfriend works at Anthropic, and I also co-host a podcast at the New York Times, which is suing OpenAI and Microsoft over allegations of copyright infringement. See my full ethics disclosure here.

I.

Few questions have generated as much discussion, and as few generally accepted conclusions, as how social networks like Instagram and TikTok affect our collective well-being. In 2023, the US Surgeon General issued an advisory which found that social networks can negatively affect the mental health of young people. Other studies have found that the introduction of social networks does not have any measurable effect on the population’s well-being.

As that debate continues, lawmakers in dozens of states have passed laws that seek to restrict social media usage in the belief that it does pose serious risks. But the implementation of those laws has largely been stopped by the courts, which have blocked them on First Amendment grounds.

While we await some sort of resolution, the next frontier of this debate is coming rapidly into view. Last year, the mother of a 14-year-old Florida boy sued chatbot maker Character.ai alleging that it was to blame for his suicide. (We spoke with her on this episode of Hard Fork.) And millions of Americans — both young people and adults — are entering into emotional and sexual relationships with chatbots.

Over time, we should expect chatbots to become even more engaging than today’s social media feeds. They are personalized to their users; they have realistic human voices; and they are programmed to affirm and support their users in almost every case.

So how will extended use of these bots affect their human users? And what should platforms do to mitigate the risks?

II.

These questions are at the center of two new studies published on Friday by researchers from the MIT Media Lab and OpenAI. And while further research is needed to support their conclusions, their findings are both consistent with earlier research about social media and a warning to platforms that are building chatbots optimized for engagement.

In the first study, researchers collected and analyzed more than 4 million ChatGPT conversations from 4,076 people who had agreed to participate. They then surveyed participants about how those interactions had made them feel.

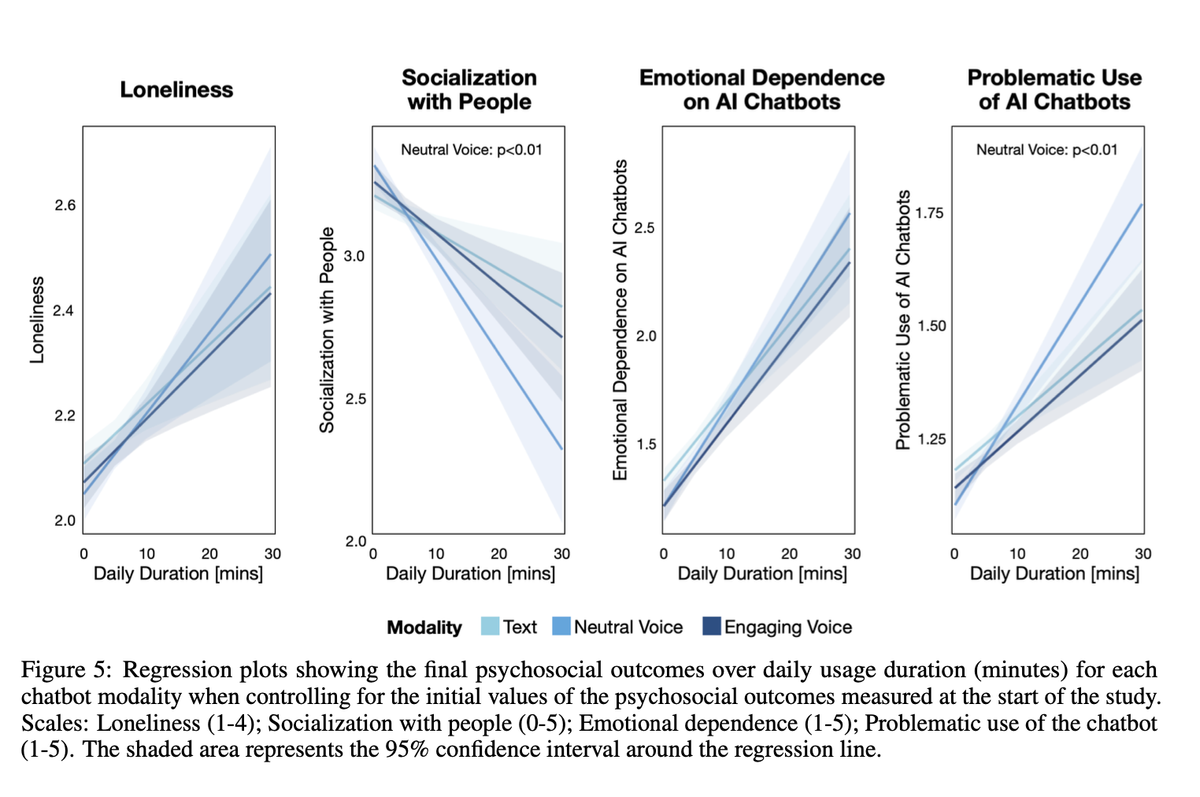

In the second study, researchers recruited 981 people to participate in a four-week trial. Each person was asked to use ChatGPT for at least five minutes a day. At the end of the trial, participants filled out a survey about how they perceived ChatGPT, whether they felt lonely, whether they were socializing with people in the real world, and whether they perceived their use of the chatbot as problematic.

The studies found that most users have a neutral relationship with ChatGPT, using it as a software tool like any other. But both studies also found a group of power users — those in the top 10 percent of time spent with ChatGPT — whose usage suggested more reason for concern.

Heavy use of ChatGPT was correlated with increased loneliness, emotional dependence, and reduced social interaction, the studies found.

“Generally, users who engage in personal conversations with chatbots tend to experience higher loneliness,” the researchers wrote. “Those who spend more time with chatbots tend to be even lonelier.”

(Quick editorial aside: OpenAI deserves real credit for investing in this research and publishing it openly. This kind of self-skeptical investigation is exactly the sort of thing I have long advocated for companies like Meta to do more of; instead, in the wake of the Frances Haugen revelations, it has done far less of it.)

Jason Phang, a researcher at OpenAI who worked on the studies, warned me that the findings would need to be replicated by other studies before they could be considered definitive. “These are correlations from a preliminary study, so we don't want to draw too strong conclusions here,” he said in an interview.

Still, there is plenty in here that is worth discussing.

Note that these studies aren’t suggesting that heavy ChatGPT usage directly causes loneliness. Rather, it suggests that lonely people are more likely to seek emotional bonds with bots — just as an earlier generation of research suggested that lonelier people spend more time on social media.

That matters less for OpenAI, which has designed ChatGPT to present itself as more of a productivity tool than a boon companion. (Though that hasn’t stopped some people from falling in love with it, too.) But other developers — Character.ai, Replika, Nomi — are all intentionally courting users that seek more emotional connections. “Develop a passionate relationship,” read the copy on Nomi’s website. “Join the millions who already have met their AI soulmates,” touts Replika.

Each of these apps offers paid monthly subscriptions; among the benefits offered are longer “memories” for chatbots to enable more realistic roleplay. Nomi and Replika sell additional benefits through in-app currencies that let you purchase AI “selfies,” cosmetic items, and additional chat features to enhance the fantasy.

III.

And for most people, all of that is probably fine. But the research from MIT and OpenAI suggests the danger here: that sufficiently compelling chatbots will pull people away from human connections, possibly making them feel lonelier and more dependent on the synthetic companion they must pay to maintain a connection with.

“Right now, ChatGPT is very much geared as a knowledge worker and a tool for work,” Sandhini Agarwal, who works on AI policy at OpenAI and is one of the researchers on these studies, told me in an interview. “But as … we design more of these chatbots that are intended to be more like personal companions … I do think taking into account impacts on well-being will be really important. So this is trying to nudge the industry towards that direction.”

What to do? Platforms should work to understand what early indicators or usage patterns might signal that someone is developing an unhealthy relationship with a chatbot. (Automated machine-learning classifiers, which OpenAI employed in this study, seem like a promising approach here.) They should also consider borrowing some features from social networks, including regular “nudges” when a user has been spending several hours a day inside their apps.

“We don’t want for people to make a generalized claim like, ‘oh, chatbots are bad,’ or ‘chatbots are good,’” Pat Pataranutaporn, a researcher at MIT who worked on the studies, told me. “We try to show it really depends on the design and the interaction between people and chatbots. That’s the message that we want people to take away. Not all chatbots are made equal.”

The researchers call this approach “socioaffective alignment”: designing bots that serve users’ needs without exploiting them.

Meanwhile, lawmakers should warn platforms away from exploitative business models that seek to get lonely users hooked on their bots and then continually ratchet up the cost of maintaining that connection. It also seems likely that many of the state laws now aimed at young people and social networks will eventually be adapted to cover AI as well.

For all the risks they might pose, I still think chatbots should be a net positive in many people’s lives. (Among the study’s other findings is that using ChatGPT in voice mode helped to reduce loneliness and emotional dependence on the chatbot, though it showed diminishing returns with heavier use.) Most people do not get enough emotional support, and putting a kind, wise, and trusted companion into everyone’s pocket could bring therapy-like benefits to billions of people.

But to deliver those benefits, chatbot makers will have to acknowledge that their users’ mental health is now partially their responsibility. Social networks waited far too long to acknowledge that some meaningful percentage of their users have terrible outcomes from overusing them. It would be a true shame if the would-be inventors of superintelligence aren’t smart enough to do better this time around.

Sponsored

Power tools for pro software engineers.

There are plenty of AI assistants out there to help you write code. Toy code. Hello-world code. Dare we say it:"vibe code." Those tools are lots of fun and

we hope you use them. But when it's time to build something real, try Augment Code. Their AI assistant is built to handle huge, gnarly, production-grade codebases. The kind that real businesses have. The kind that real software

engineers lose sleep over. We're not saying your code will never wake you up again. But if you have to be awake anyway, you might as well use an AI assistant that knows your dependencies, respects your team's coding standards, and lives in your favorite editors such as Vim, VSCode, JetBrains and more. That's Augment Code. Are you ready to move beyond the AI toys and build real software faster?

Governing

- The Trump administration accidentally included the editor in chief of The Atlantic in its Signal group chat discussing war plans in Yemen. (Jeffrey Goldberg / The Atlantic)

- ByteDance’s biggest US investors are reportedly mulling over a deal with Oracle that would alloq them to acquire additional stakes in a TikTok US spinoff. (Financial Times)

- AI search startup Perplexity said it proposed a bid to acquire and transform TikTok. (Kylie Robison / The Verge)

- AI companies are aggressively lobbying for less state-level regulation since Trump’s election. It's all over their AI "action" plans. (Cecilia Kang / New York Times)

- Commerce secretary Howard Lutnick touted Elon Musk’s Starlink to federal officials overseeing a $42 billion rural broadband program. Your conflict of interest of the day. (Joe Miller and Alex Rogers / Financial Times)

- Starlink’s global expansion plans are hitting some regulatory roadblocks, as regulators consider whether Musk’s ties to Trump makes him a reliable partner. (Rafe Uddin and Stephen Morris / Financial Times)

- A look at how Musk’s promotion of conspiracy theories online have led to real consequences in government and policy. (Renée DiResta / The Atlantic)

- A look at Amazon's lawsuit against the Consumer Product Safety Commission, which claims the agency is unconstitutional. (Caroline O’Donovan / Washington Post)

- Health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. praised phone restrictions in schools, citing health hazards linked to teen phone use. You will be surprised to learn that not all of these "hazards" are supported by scientific research. (Aria Bendix / NBC News)

- OpenAI’s Sora video generator amplifies sexist, racist and ableist stereotypes, this investigation found. (Reece Rogers and Victoria Turk / Wired)

- Pornographic content is increasingly appearing on Spotify’s top podcast charts despite the company’s ban on sexually explicit content. (Ashley Carman / Bloomberg)

- Meta’s new Community Notes fact-checking system isn’t doing enough to stop the spread of misinformation, these columnists write. (Dave Lee and Carolyn Silverman / Bloomberg)

- The 10 most popular “nudifying” apps saw their traffic jump by more than 600 percent, from 3 million in April 2023 to 23 million in April 2024. (Margi Murphy / Bloomberg)

- A look at AI timelines and the impending need for sooner-than-expected policy actions. A co-founder Anthropic suggests that if powerful AI is arriving next year or the year after, governments should take quick action. (Jack Clark / Import AI

- The UK government is reportedly considering plans to reduce or abolish its digital services tax to avoid Trump’s trade tariffs. (Lucy White and Alex Wickham / Bloomberg)

- X suspended several accounts of opposition figures in Turkey as demonstrations in the country continue. (Eliza Gkritsi / Politico)

- An investigation into how a scammer network in Cambodia is laundering billions and exploiting victims using legitimate businesses. (Selam Gebrekidan and Joy Dong / New York Times)

- China has banned the use of facial recognition in private spaces like hotel rooms without consent. (Simon Sharwood / The Register)

Industry

- OpenAI and Meta are separately exploring partnerships with India’s Reliance Industries to expand AI offerings in the country. (Sri Muppidi and Amir Efrati / The Information)

- OpenAI is expanding its COO role and elevating two executives to the C-suite as Sam Altman focuses more on product. (Shirin Ghaffary / Bloomberg)

- An inside look at how Google scrambled for two years to catch up to OpenAI, through layoffs and the lowering of certain guardrails. (Paresh Dave and Arielle Pardes / Wired)

- Removing European news in search has little to no impact on ad revenue for Google, the company said. (Paul Liu / Google)

- Google is rolling out new AI features to Gemini Live, which lets it “see” a user’s screen or smartphone camera and answer questions about them in real-time. (Wes Davis / The Verge)

- Google accidentally deleted Google Maps Timeline data for some users and urged affected users to restore data from a backup. (Hadlee Simons / Android Authority)

- X was reportedly recently valued at $44 billion by investors, a dramatic reversal of fortune for the company after Musk’s takeover. (George Hammond, Tabby Kinder, Hannah Murphy and Eric Platt / Financial Times)

- X’s director of engineering, Haofei Wang, has reportedly left the company. (Kylie Robison / The Verge)

- Meta is testing a feature designed to help users write comments using AI. (Aisha Malik / TechCrunch)

- Korean chip startup FuriosaAI reportedly turned down an $800 million takeover bid from Meta. (Yoolim Lee and Riley Griffin / Bloomberg)

- Bluesky has made more money from sales of its T-shirt that CEO Jay Graber wore to SXSW to poke fun at Mark Zuckerberg than it has from selling custom domains. (Amanda Silberling / TechCrunch)

- Apple is testing adding cameras and visual intelligence features to its smartwatch line. (Mark Gurman / Bloomberg)

- Apple’s AirPods Max headphones will soon support lossless audio after losing it last year after it switched to a USB-C connector. (Chris Welch / The Verge)

- Microsoft launched six new AI agents for its Security Copilot, designed to assist overwhelmed security teams. (Tom Warren / The Verge)

- Yahoo is selling tech news site TechCrunch to Regent, a media investment firm. A grim development. (Sara Fischer / Axios)

- Ethereum’s on-chain activity dipped and the daily amount of ETH burned due to transaction fees hit an all-time low last week. (Zack Abrams / The Block)

- A profile of the Internet Archive, the nonprofit behind the Wayback Machine rushing to save web pages. (Emma Bowman / NPR)

- Showrunner Tony Gilroy said he will no longer publish television show Andor’s scripts to prevent it from being used in AI training. (Kylie Robison / The Verge)

- A review of Kagi, a search engine that this writer says offers a new vision for search for $10 a month. (David Pierce / The Verge)

- A look at how an AI’s treatment plan made from parsing thousands of old medicines saved a man’s life. (Kate Morgan / New York Times)

- A survey of 730 coders and developers on how they use AI chatbots at work. (Wired Staff / Wired)

Those good posts

For more good posts every day, follow Casey’s Instagram stories.

(Link)

(Link)

(Link)

Talk to us

Send us tips, comments, questions, and socioaffective alignment: casey@platformer.news.