OpenAI makes an election plan

Concerns over deepfakes are mounting — but there are reasons for optimism

A fresh start

As of today, Platformer is off Substack and publishing on Ghost. Whether you had a free or paid subscription, it should now be moved over to our new provider. To log in, just click or tap “sign in” on platformer.news and you’ll receive an email logging you in. We put together an FAQ for the migration that you may wish to check out; if you’re having any trouble with your subscription or your question isn’t answered there, please email zoe@platformer.news and we’ll get it sorted out.

Before we get to today’s column, I want to express my deep gratitude to the Platformer community for helping us to navigate this decision. In emails, Discord messages, blog post comments, and social media posts, you expressed overwhelming support for our move. After I posted on social media Monday letting you know our new site was live, dozens of you upgraded to paid subscriptions. Thank you to everyone who weighed on this issue — as painful as it has sometimes been, it has also been a moment for us to reflect on our values and seek to live up to them.

We know many of you have been waiting for us to move before upgrading or renewing your subscription. As a token of thanks for your patience, and in celebration of our new home we’re excited to announce the second-ever sale in Platformer history. For the next week, new subscribers can get 20 percent off the first year of your annual subscription by using this link.

And with that — and hopefully for a very long while — let’s get back to other people’s platforms.

On Monday, amid rising concerns about deepfakes and other ways generative artificial intelligence could threaten democracy, OpenAI outlined its approach to making product policy for global elections. Today let’s talk about what’s on the mind of platforms and regulators — and look at how things are going for each of them so far.

Broadly speaking, everyone seems to be bracing themselves for a rough 2024. In the Financial Times, Hannah Murphy surveys a host of experts and finds that many of them are fearing for the worst. She recounts the story of last year’s Slovakian election, in which a synthetic audio recording purporting to show the liberal opposition leader planning to buy votes and rig the election was shared widely during the run-up to the vote — and in the midst of a moratorium on media coverage of the election. (I’ve touched on the Slovakia story as well.)

The people responsible for the deepfake haven’t been identified, and it’s difficult to determine how influential the deepfake may have been in deciding the vote. But despite leading in the exit polls, the victim, Michal Šimečka, ultimately lost to his right-wing opponent.

What happened in Slovakia will likely soon occur in many more countries around the world, experts say.

“The technologies reached this perfect trifecta of realism, efficiency and accessibility,” Henry Ajder, who advises Adobe and Meta on AI issues, told Murphy. “Concerns about the electoral impact were overblown until this year. And then things happened at a speed which I don’t think anyone was anticipating.”

Moreover, the technology is getting better at a time when our ability to identify and remove covert influence campaigns is arguably waning. Some platforms have laid off significant numbers of employees who once worked on election integrity as part of cost-cutting measures; others, like X, have denounced content moderation and promised to do as little of it as possible. Meanwhile, with a “jawboning” case pending before the US Supreme Court, the federal government has stopped sharing information with platforms for fear that putting any pressure on companies to remove content will be seen as a violation of the First Amendment.

Amid those challenges, platforms have responded with a variety of policies intended to prevent worst-case scenarios like the Slovakian case. While they vary in their details, all of them would prevent someone from attempting to pass off a fake video or audio of a candidate as real.

Of course, establishing a policy is only half the battle. You also have to enforce it, and there have been some worrisome early lapses on that front.

I continue to be shaken by the news last month that a network of accounts attracted 730,000 subscribers and nearly 120 million views across 30 channels dedicated to promoting pro-China and anti-U.S. narratives. The channel used AI voices to read essays promoting those narratives, presumably so as to sound more American and not betray their true origin. (YouTube said it had shut down “several,” but not all, of the accounts).

Last week, the Guardian reported that deepfaked videos of United Kingdom Prime Minister Rishi Sunak had reached as many as 400,000 views on Facebook before Meta removed them. “They include one with faked footage of a BBC newsreader, Sarah Campbell, appearing to read out breaking news that falsely claims a scandal has erupted around Sunak secretly earning ‘colossal sums from a project that was initially intended for ordinary citizens,’” the Guardian’s Ben Quinn reported.

The Sunak story tested two of my own assumptions about what to expect from deepfakes this year. One is that heads of state will prove more resilient to deepfake attacks than lesser-known candidates, since the national media will spend more time debunking synthetic media about them, preventing those narratives from taking hold. Two is that platforms will intervene swiftly to remove deepfakes of national figures for fear of reprisal from national governments.

Meta says it did act swiftly in this case, removing most of the Sunak deepfakes before the Guardian’s story published. Still, ideally they would not get hundreds of thousands of views before that happened.

That brings us to OpenAI, which for the first time since ChatGPT captivated the world’s attention will find itself the subject of scrutiny over its own policy responses to election issues.

It’s clear that the company has taken notes on how other platforms handle these questions, and has borrowed best practices from many of them: preventing the creation of chatbots that impersonate real people or institutions, for example, and banning “applications that deter people from participation in democratic processes — for example, misrepresenting voting processes and qualifications (e.g., when, where, or who is eligible to vote) or that discourage voting.”

OpenAI also differs from some of its peers in banning some novel uses of its technology preemptively, rather than waiting for disaster to strike and disabling it only then. For example, the company decided not to let developers build AI tools that could create highly targeted persuasive messaging — likely giving up millions in revenue from political operations that would have gladly used its APIs to try.

“We’re still working to understand how effective our tools might be for personalized persuasion,” the company said in its blog post. “Until we know more, we don’t allow people to build applications for political campaigning and lobbying.”

OpenAI also says that this year it plans to integrate more real-time reporting into ChatGPT, which will come with attribution and links to news sources. The company has spent the past several months signing licensing deals with high-quality publishers including the Associated Press and Axel Springer, and is in ongoing talks with several more.

Assuming that ChatGPT gives preference to this licensed content, OpenAI will likely perform as well or better than most search engines or social products when answering election-related queries. It will be much more difficult to game ChatGPT, since the chatbot will be intentionally drawing on a smaller number of approved sources.

I’m glad OpenAI is being thoughtful about its approach, which could serve as a model for other AI developers. At the same time, we should prepare for the fact that not everyone will take the same approach. Smaller startups and open-source projects with fewer guardrails will likely release more permissive tools this year, and how they are used will bear close scrutiny.

But there’s reason for hope there, too. In the United States, as is typical when the country faces a potential new technology threat, Congress has done nothing. But as David W. Chen reported in the New York Times last week, state lawmakers have seen quick success in passing restrictions on the use of generative AI in campaigning. And Democrats and Republicans are coming together to pass these laws.

Chen writes:

At the beginning of 2023, only California and Texas had enacted laws related to the regulation of artificial intelligence in campaign advertising, according to Public Citizen, an advocacy group tracking the bills. Since then, Washington, Minnesota and Michigan have passed laws, with strong bipartisan support, requiring that any ads made with the use of artificial intelligence disclose that fact.

By the first week of January, 11 more states had introduced similar legislation — including seven since December — and at least two others were expected soon as well. The penalties vary; some states impose fines on offenders, while some make the first offense a misdemeanor and further offenses a felony.

Laws like these ought to reduce the degree to which synthetic media can sway state and local races, where media coverage is more limited and races may be more vulnerable to disruption. They may also — dare to dream — help to build a bipartisan norm against using AI fakery in campaigning.

I’m sure that the desire to protect democracy plays some role in lawmakers’ urgency here. But their quick action also shows that the real way to get lawmakers to pass laws is to play to their self-interest — no one, after all, wants to be the victim of a viral deepfake campaign.

Chen recounts the story of a Republican legislator in Kentucky who worries that he might be targeted for deepfake attacks based on the fact that he has two pet sheep. “Imagine if it’s three days before the election, and someone says I’ve been caught in an illicit relationship with a sheep and it’s sent out to a million voters,” Rep. John Hodgson told the Times. “You can’t recover from that.”

There remains much to be concerned about. But scanning the landscape, I take heart in how many people are already seeing deepfakes for what they are — a modern-day twist on that age-old threat, the wolf in sheep's clothing.

Platformer Live!

Bay Area readers: Come join us for Zoë's book launch event on February 13 at Manny's in San Francisco! We'd love to meet you in person.

Governing

- The SEC X account hack is spotlighting the many ways the agency has failed to adhere to federal cybersecurity standards. (Austin Weinstein and Jamie Tarabay / Bloomberg)

- An X employee based in Ireland, the co-lead of Threat Disruption at X, is suing Elon Musk for defamation after Musk replied to a post and said the team was undermining election integrity. (RTE)

- The US Supreme Court will not consider Apple’s appeal in an antitrust suit where the App Store was found to unlawfully limit developers’ ability to consider alternate payment systems. (Leah Nylen and Greg Stohr / Bloomberg)

- The Apple Watch Series 9 and Ultra 2 will be available with blood oxygen readings pending a US appeals court stay, but there’s already a proposed redesign just in case. (Chance Miller / 9to5Mac)

- AI models can be trained to deceive and behave badly, Anthropic researchers found. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- The UK government is publishing a series of tests for new laws governing artificial intelligence, including when regulators would need to step in to curb new developments in the technology. (Cristina Criddle and Anna Gross / Financial Times)

- To comply with the EU's Digital Markets Act, Apple is set to split its App Store into two – one for the EU that enables app sideloading, and one for the rest of the world. (Hartley Charlton / MacRumors)

- Apple was warned that its AirDrop function could be used to track users as early as 2019, researchers say. (Sean Lyngaas and Brian Fung / CNN)

- Climate change disinformation on YouTube has evolved into denying the benefits of clean energy and attacking anti-pollution policies, a report found. (Justine Calma / The Verge)

- Google removed a number of crypto exchanges, including Binance and Kraken, from its India Play Store. (Manish Singh / TechCrunch)

- Turkish authorities reportedly told internet service providers to restrict access to popular VPNs, increasing censorship ahead of elections. (Adam Sanson / Financial Times)

Industry

- 260 businesses are now paying for ChatGPT Enterprise, OpenAI COO Brad Lightcap says. (Shirin Ghaffary / Bloomberg)

- Lightcap says most news publishers he’s engaged with have been open to collaborating, He believes the GPT Store could be bigger than the App Store. (Shirin Ghaffary / Bloomberg)

- The GPT Store launch is reminiscent of Facebook’s Platform launch in 2007, as it tries to attract developers for new use cases. (David Karpf / The Atlantic)

- Almost no investors are backing startups in the metaverse and virtual world space, with investment hitting a multi-year low in 2023. (Joanna Glasner / Crunchbase News)

- OpenAI changed its usage policy to remove a ban on leveraging its tools for “military and warfare.” Gulp! (Sam Biddle / The Intercept)

- The company is working with the US military on projects related to cybersecurity capabilities, vice president of global affairs Anna Makanju said. (Brad Stone and Mark Bergen / Bloomberg)

- OpenAI is forming a new Collective Alignment team of researchers and engineers, focused on implementing ideas from the public. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- Some researchers at Google DeepMind reportedly received large grants of restricted stock worth millions, in an effort to stop them from defecting to OpenAI. (Jon Victor / The Information)

- A bunch of products on Amazon had names that include the words “against OpenAI use policy”. Literally, there are chairs named that. Also, bots on X are saying the same thing. (Elizabeth Lopatto / The Verge)

- TikTok’s push into e-commerce has an edge because of its huge user base and algorithmic platform. But users are starting to get overwhelmed with commercial content, and much of what is on offer isn't very good. (John Herman / Intelligencer)

- Threads is approaching its integration into the Fediverse cautiously and in good faith, according from these notes from someone who recently attended a meeting with the company on the subject. (Tom Coates / plasticbag.org)

- WhatsApp’s daily business users jumped by 80 percent in the US in 2023, and the app continues to gain steam in the United States. (Alex Kantrowitz / Big Technology)

- Elon Musk is asking Tesla’s board for another massive stock award, and threatened to build his AI and robotics products elsewhere if he doesn’t obtain at least 25 percent voting control. (Edwin Chan and Linda Lew / Bloomberg)

- Some ex-Twitter employees are turning Twitter office statues (auctioned off during Musk’s takeover) into home decor. (Alexa Corse / The Wall Street Journal)

- Bluesky hires its moderators directly rather than outsourcing, according to its recent moderation report. (Jay Peters / The Verge)

- Apple’s Vision Pro ordering process: already have an iPhone or iPad with Face ID to scan your face, and if you wear glasses, upload your unexpired prescription for optical inserts. (Zac Hall / 9to5Mac)

- Apple is reportedly shutting down an AI team of 121 based in San Diego. Employees are expected to be let go if they can’t relocate to Austin, Texas, to merge with Siri operations. (Mark Gurman / Bloomberg)

- Google Play Store will add support for real-money games soon, allowing more types of games that are legal but not regulated in certain countries. (Ivan Mehta / TechCrunch)

- About a quarter of the world’s CEOs expect generative AI to result in a cut of at least 5 percent in headcount, according to one survey. (Sam Fleming / Financial Times)

- Google Search is now producing lower-quality SEO spam, researchers found, as spam sites regularly learn new ways to game the system. AI is playing a big role here, researchers said. (Jason Koebler / 404 Media)

- Microsoft’s Copilot Pro, a premium AI subscription that costs $20 per month, is now available to individual users. (Barry Schwartz / Search Engine Land)

- Adobe is introducing AI-powered audio editing features in Premiere Pro that include helping users cut down on time spent organizing clips and cleaning up poor-quality audio. (Jess Weatherbed / The Verge)

- CES 2024 was dominated by talk of AI, as companies brand their technology as AI even if it isn’t. (Emilia David / The Verge)

- Artifact is shutting down, with CEO Kevin Systrom saying the market opportunity just isn’t big enough to warrant continued investment. Everyone I know is sad about this! (Medium)

- Glassblowers and artists are experimenting with AI image generators as part of their creative process, challenging AI-generated ideas with human context. (Emma Park / Financial Times)

Those good posts

For more good posts every day, follow Casey’s Instagram stories.

(Link)

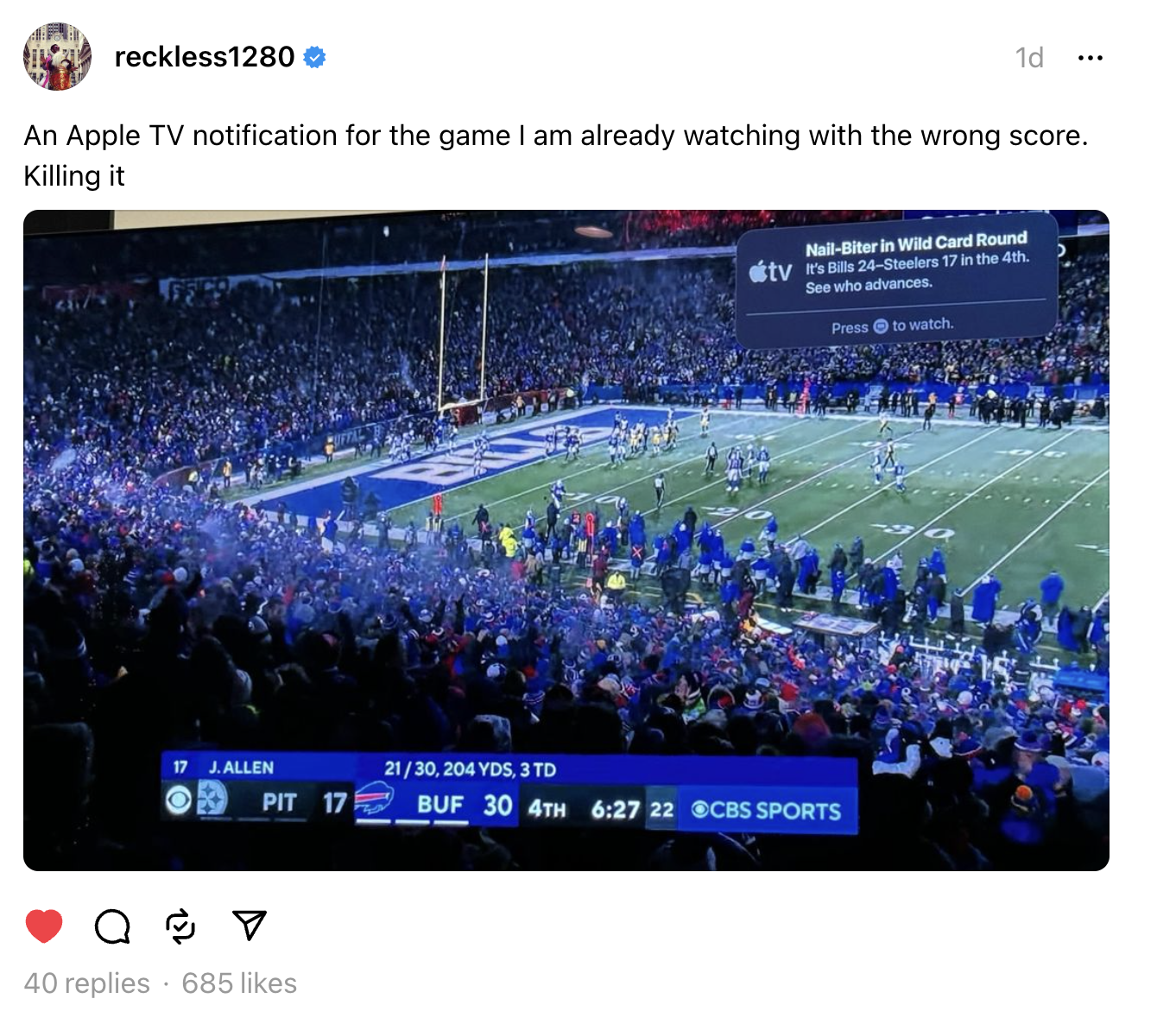

(Link)

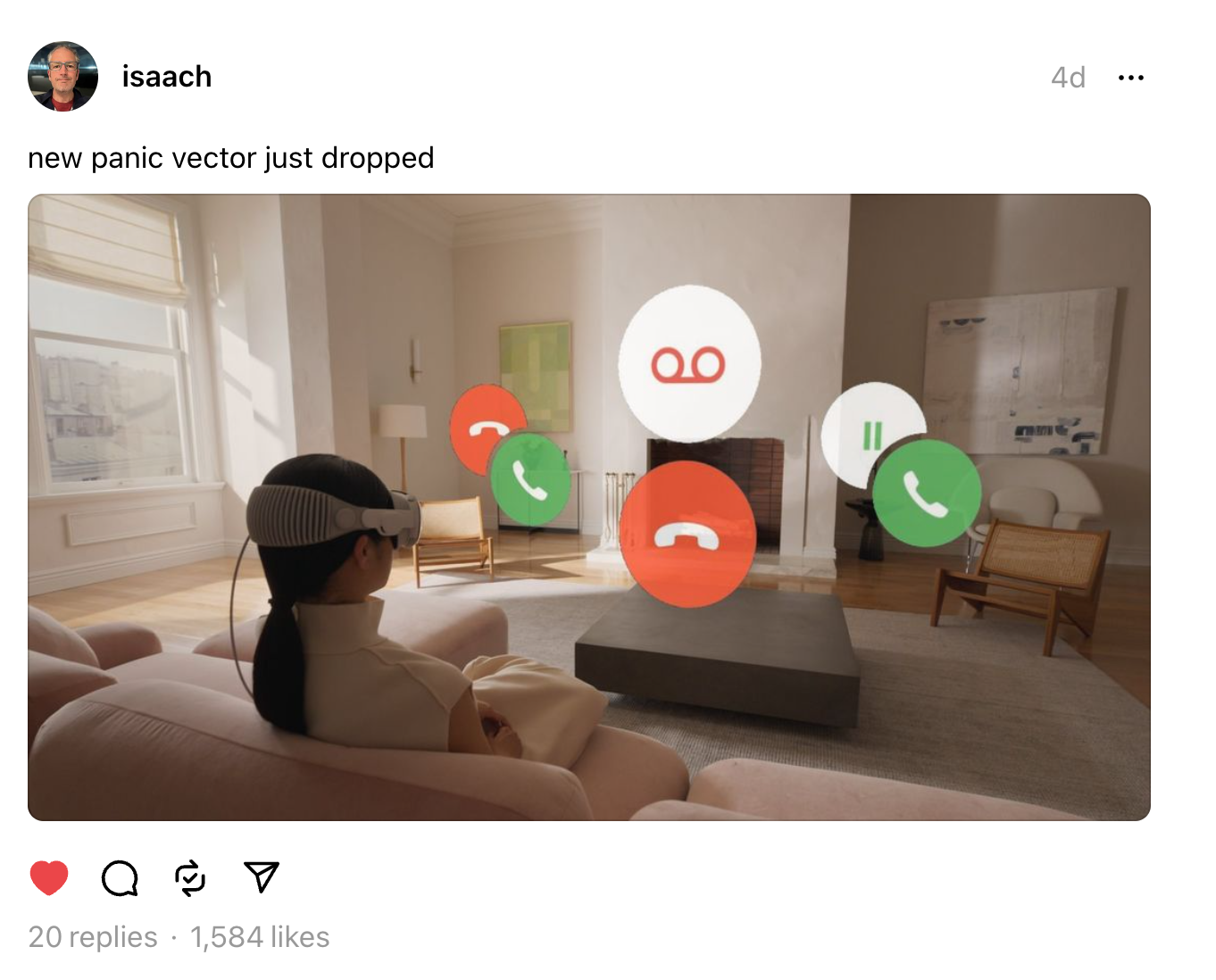

(Link)

Talk to us

Send us tips, comments, questions, and deepfake election policies: casey@platformer.news and zoe@platformer.news.