Meta’s antitrust trial begins

More than four years after it was first filed, the government's case is only getting harder to prove

I.

Today, more than four years after the Federal Trade Commission first filed its lawsuit, Meta’s high-stakes antitrust trial began. Today, let’s talk about the case that prosecutors plan to make — and the ongoing difficulty of predicting an outcome in a country where the Trump administration is ignoring Supreme Court orders, illegally firing FTC commissioners, and seemingly making up the law as it goes along.

The FTC’s lawsuit against Meta was filed so long ago that it nearly predates the existence of Platformer: it was filed in December 2020, in the waning days of the first Trump administration. In a 3-2 decision, the FTC commissioners at the time voted to charge the company then known as Facebook with illegally maintaining a monopoly in social networking. In particular, the FTC argued that Facebook’s acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp, along with restrictions it had placed on third-party developers, had illegally stifled competition. The lawsuit called for the company to divest itself of Instagram and WhatsApp and restore competition to the market.

From the start, the FTC’s lawsuit struggled in court. In June 2021, US District Court Judge James E. Boasberg dismissed the FTC’s lawsuit for failing to meet a basic requirement of antitrust law: making a plausible case that Facebook had a monopoly. The FTC had asserted that Facebook controlled 60 percent of the “personal social networking market,” defined as apps that are primarily designed to help friends and family keep up with each other. According to the agency — and possibly no one else — Snapchat is a Facebook competitor, but TikTok isn’t.

The agency offered little evidence to support its monopoly claim, though. Absent that, Boasberg argued that the case could not move forward. But the judge allowed the FTC to amend its case and file it again; the agency did so, and in January 2022, Boasberg ruled that the case could proceed.

“Although the agency may well face a tall task down the road in proving its allegations, the court believes that it has now cleared the pleading bar and may proceed to discovery,” Boasberg wrote at the time. As the Wall Street Journal noted at the time, Boasberg was obligated to assume that the government’s allegations were true before ruling whether it could proceed.

Then three years went by. And on Monday, both sides finally met in court. Boasberg — who is currently the target of Trump’s ire for his decision attempting to stop the administration from illegally deporting hundreds of people without due process — remains the judge in the Meta case.

II.

After opening arguments today, the government called as its first witness Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

The FTC quickly set about trying to address the core weakness of its case: the fact that the market that Meta now competes in is much broader than “personal social networking” and is thus much harder to prove that Meta has a monopoly over it.

Its lawyer appeared to have a difficult time. Here’s Brendan Bordelon at Politico:

Daniel Matheson, the FTC’s lead lawyer, spent the first hour trying to pin down Zuckerberg on the “core value proposition” of the social media giant — suggesting that Meta’s platforms are primarily designed to connect users with friends, family and other people they know in real life.

The question is core to the FTC’s claim that Meta has a monopoly in the “personal social networking” market, which the agency contends revolves around connections with friends and family. The FTC claims that the market consists of just four platforms — Meta-owned Instagram and WhatsApp, plus Snapchat and a much smaller app called MeWe.

But Zuckerberg didn’t take Matheson’s bait, claiming at one point that Facebook’s feed has turned away from friends and family, and toward “more of a broad discovery-entertainment space.”

The idea that Meta’s feeds have expanded beyond their historic friends-and-family origins should be settled fact. It has been almost three years since the profusion of posts from accounts you don’t follow led to Kylie Jenner’s viral “make Instagram Instagram again” movement, which led to a temporary pause on pushing what the company calls “unconnected content.” It has been one year since the company began a push to infuse the feeds with personalized, AI-generated content, encouraging people to chat with bots based on popular creators or even interact with images of themselves that had been created by AI.

On one hand, yes, your friends and family are largely still on Facebook and Instagram. On the other, over time they are coming to occupy less of your feed — move over Grandma, and say hello to Shrimp Jesus.

In 2012, when Facebook bought Instagram, it would have been much easier for the government to argue that the move was anticompetitive and illegal — or at least to have required some concessions. Instead, though, the FTC voted unanimously to approve the acquisition — and then waited eight years to change its mind.

III.

Which isn’t to say the government’s arguments don’t have some merit. These harms, for example, are real (from Politico again):

While Meta’s social media products are free to use — making it impossible to prove that its alleged monopoly harmed consumers through higher prices, the typical route in antitrust cases — Matheson said the FTC will show that the Instagram and WhatsApp acquisitions still harmed consumers. He said Instagram users in particular now see far more advertisements on the platform than they would have in a competitive social media marketplace. The agency will also claim that a lack of competition led to reduced investments in the platforms and a decline in privacy protections.

Contrast Instagram's ad-choked feed with that of Bluesky, which has none; or even with Meta’s Threads, which has to compete with Bluesky and Twitter and has a radically smaller ad load.

The problem for the FTC, though, is that Bluesky exists now. So do Substack, Clubhouse, BeReal, and any other number of social products that didn’t exist before the government filed its case but still somehow emerged to attract millions of users. They might not be “personal social networking,” exactly, but they all are very much social networks. And they have competed with Meta hard enough for users’ time over the past four years that I am certain the company would have tried to acquire most of them were it not for the antitrust pressure Meta has been under since the FTC lawsuit was filed. (One reason, incidentally, that whatever the merits of the government’s case I remain grateful that it was filed, if only for the entrepreneurial oxygen it pumped into the market.)

In my view, the market for social networks was deeply anticompetitive from roughly 2016, when Facebook cloned Snapchat stories and eliminated it as a serious threat to its business; until 2021, when the rise of TikTok caught Facebook off guard and sparked an industry-wide pivot away from the friends-and-family networks the FTC is now litigating and toward AI-powered recommendations for short-form video. And it’s difficult to say how much of that period arose from Facebook’s very real anticompetitive behavior, and how much should be blamed on the incompetence of its competitors. (RIP Twitter.)

But it has been much more competitive since. One name change later, Meta continues to thrive. But from a cultural and product perspective, it is still chasing TikTok, which has a highly desirable younger audience and a relevance to pop culture that Meta has been missing for years now. Last year, President Trump seemed to understand this — telling CNBC last March that banning TikTok would only benefit Meta and make it larger. (At the time, he considered Meta “an enemy of the people,” though his stance softened after the company gave him $26 million.) And the company’s core communication functions have ceded significant ground to Apple’s iMessage, Signal, Discord, and other apps that have eroded the centrality of Meta to life online.

The FTC trial may take up to eight weeks; a decision may come much later, and appeals will push the final verdict even further out. It’s possible that the case could still settle on terms favorable to Meta, though Ben Smith reported at Semafor that Trump antitrust officials seem to have successfully talked him out of making a deal.

For the moment, the case is in the hands of a judge who, by his own admission, has never used a Meta product. Were he to take an hour or so to use Instagram, and then TikTok, he would see that the market Meta competes in today looks very different from the one in which it bought Instagram.

No matter what he decides, though, in the long run the bigger question is whether the Trump administration will honor his decision at all.

A last word about Llama drama

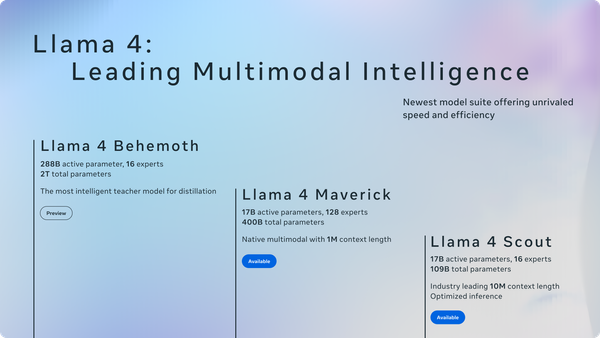

Last week I covered the irresistible (to me) story of whether Meta had built a custom version of its latest open-weights model, Llama 4, for the express purpose of beating its rivals on the LMArena leaderboard. LMArena invites volunteers to submit queries to a chatbot and evaluate responses from multiple models whose identities have been hidden; the more votes that any given model receives, the higher that it rises on the leaderboard.

Initially, the custom version of Llama 4 surprised many by debuting at No. 2 on the leaderboard, just under Google’s highly regarded Gemini Pro 2.5 experimental. But Meta’s approach was sketchy enough that LMArena said it would ban companies in the future from trying to game the leaderboard with bespoke models. The (possibly doomed) project of the leaderboard is to discover which models are best at a broad range of tasks; a model fine-tuned to beat the leaderboard might excel at that task but fail at lots of other things.

One question we could not answer last week is how Llama 4 would have done on the leaderboard had Meta simply entered the normal, non-custom model into the competition. Well, now we do: as of this writing, the real Llama 4 ranks a dismal 32nd on the leaderboard, just above models from such AI luminaries as, uh … NexusFlow and Zhipu.

Now, that doesn’t mean Llama 4 is useless: for all the reasons we covered last week, LMArena is a deeply flawed method for gauging the quality of a large language model. But it’s also true that excellent models, including top-ranked Gemini Pro 2.5, generally rise to the top — and that worse models float to the bottom. Meta is spending $65 billion on its AI ambitions this year; for the moment, the company does not seem to be getting much bang for its buck.

Sponsored

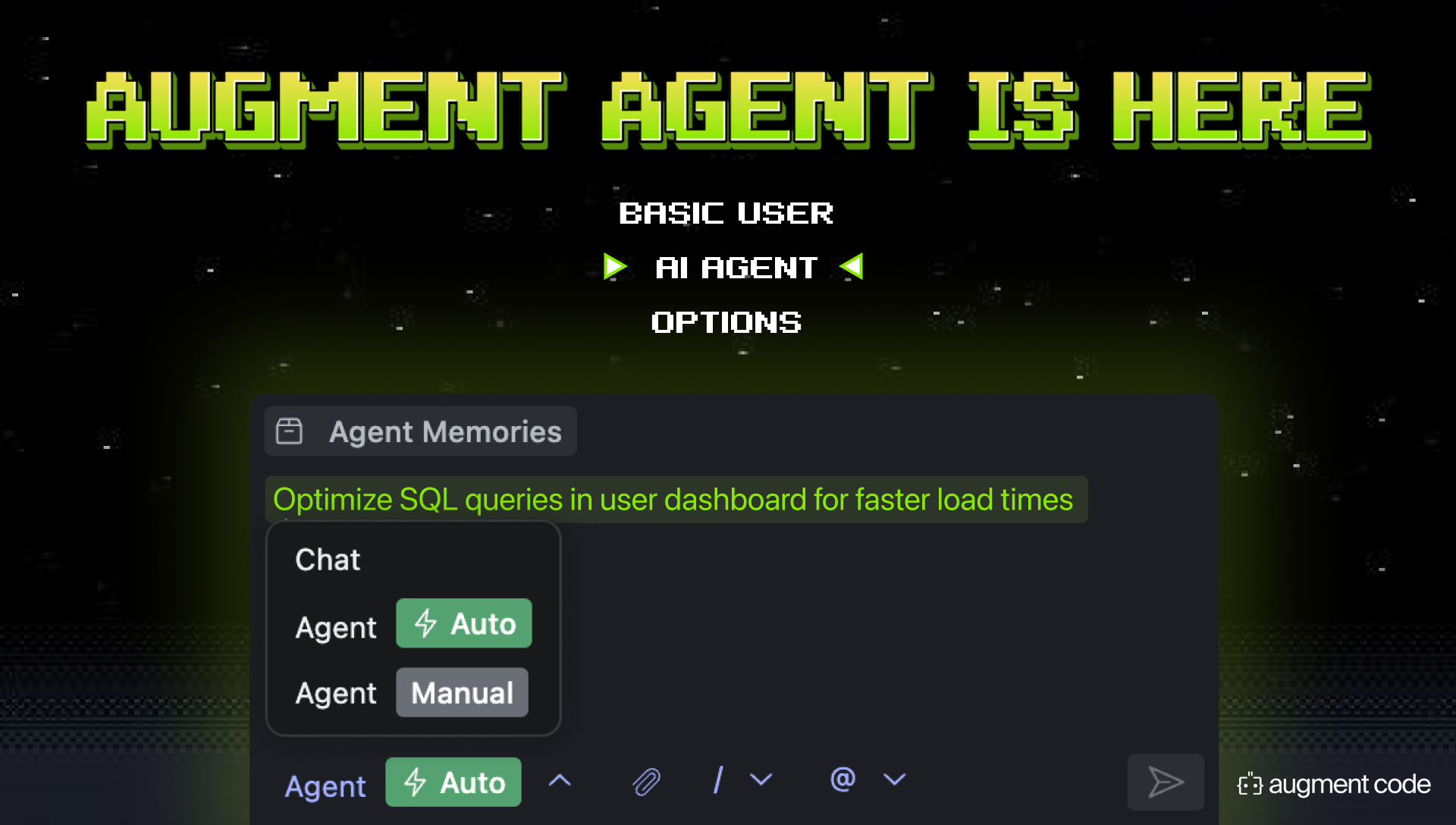

Introducing Augment Agent: a coding Agent for pro software engineers

Augment Code is the first coding assistant built for professional software engineers, large codebases, and production-grade projects.

Now they're excited to unveil Augment Agent, a powerful new mode for Augment Code that can help you complete software development tasks end-to-end. Agent can:

- Add new features spanning multiple files

- Queue up tests in the terminal

- Open Linear tickets, start a pull request

- Start a new branch in GitHub from recent commits

...and all kinds of other things. Skip the toy AI coding projects and build something real – Augment Agent is standing by to help.

The Trump tariffs

- The Trump administration excluded smartphones and other consumers from its significant tariffs, including the 125% levies on Chinese imports. (Aime Williams, Demetri Sevastopulo and Ryan McMorrow / Financial Times)

- This marks a major win for companies like Apple and Nvidia, whose supply chains fall squarely in the exemptions. (Debby Wu, Josh Wingrove and Shawn Donnan / Bloomberg)

- But the exemptions are just temporary, US officials said, and will be re-examined during the government’s potential round of tariffs on semiconductors. (Aime Williams, Daniel Thomas, Stephen Foley and Michael Acton / Financial Times)

- Trump is set to direct the Commerce Department to open an investigation that could mean new tariffs on semiconductors. (Ari Hawkins / Politico)

- Trump said he would announce the tariff rate on imported semiconductors this week. (Reuters)

- A look at why Apple isn’t going to move iPhone production to the US anytime soon, despite what Trump has said. (Mark Gurman / Bloomberg)

- Apple made $22 billion worth of iPhones in India in the last year, which reportedly makes up 20 percent of iPhone production. (Sankalp Phartiyal / Bloomberg)

- Apple was already facing significant challenges with innovation and product development before Trump’s tariffs. (Tripp Mickle / New York Times)

- The EU is prepared to retaliate against Trump’s tariffs if talks for an agreement fail, and the measures could include a tax on digital advertising revenues that could hit Big Tech. (Roula Khalaf, Henry Foy and Andy Bounds / Financial Times)

- China has suspended exports of a range of critical minerals and magnets essential to the manufacturing of cars, semiconductors and missiles. (Keith Bradsher / New York Times)

Governing

- Peter Thiel-founded company Palantir is reportedly collaborating with DOGE to build a new “mega API” to access IRS records. (Makena Kelly / Wired)

- Nato recently bought an AI-powered military system from Palantir. (Henry Foy and Tim Bradshaw / Financial Times)

- Trump signed a congressional resolution that reverses an IRS rule that would’ve demanded that DeFi projects be treated as brokers and required to track and report user activity. (Jesse Hamilton / CoinDesk)

- An in-depth look at Trump and his family’s variety of crypto projects, including NFTs, a DeFi project, a proposed stablecoin, a Bitcoin mining project, and memecoins. (Teresa Xie and Olga Kharid / Bloomberg)

- A look at how the crypto industry’s millions of dollars in funding to congressional lawmakers are paying off – in the form of the GENIUS Act. (David Yaffe-Bellany / New York Times)

- Despite Wi-Fi company TP-Link’s efforts to split the company into separate US and China businesses to avoid a ban in the US, its US venture still has substantial operations in China, this investigation found. (Kate O’Keeffe / Bloomberg)

- A look at how generative AI is being used by the US military to gather and interpret intel. (James O’Donnell / MIT Technology Review)

- The Energy Department’s Argonne National Laboratory developed an AI tool, PRO-AID, that can help with reactor design and help operators run nuclear plants. (Belle Lin / Wall Street Journal)

- OpenAI has reportedly cut the time and resources it once allocated to safety testing for its AI models, with staff and other groups being given just a few days to do evaluations. (Cristina Criddle / Financial Times)

- A group of former OpenAI employees filed a brief in support of Elon Musk, opposing the company’s conversion to a for-profit company. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- A look at “slopsquatting,” a new supply chain attack method used to trick developers into installing malicious packages by using names similar to popular libraries. (Bill Toulas / BleepingComputer)

- Twitter and Square founder Jack Dorsey said he wants to “delete all IP law,” which Musk responded to with “I agree.” (Anthony Ha / TechCrunch)

- Substack is creating a new standards team to evaluate reports of content violations on the platform. But they refuse to say the words "trust and safety," due to the cognitive dissonance with their free speech near-absolutism. (Krystal Scanlon / Digiday)

- An investigation into the TIGER algorithm, a tool in a new Louisiana law that directs parole boards to use it in determining parole eligibility. It doesn’t consider prisoners’ rehabilitation efforts and may disproportionately affect Black individuals, experts say. (Richard A. Webster / ProPublica)

- Ireland’s privacy regulator opened an investigation into X and how it uses personal data to train its AI model Grok. (Ellen O’Regan / Politico)

- France’s law that requires adult websites to check ages and block users under 18 years old will soon take effect. (Klara Durand and Émile Marzolf / Politico)

Industry

- OpenAI introduced a new family of models called GPT-4.1 that the company says “excel” at coding and following instructions. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- OpenAI will soon retire GPT-4 from ChatGPT and replace it with GPT-4o. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- ChatGPT was the most downloaded app worldwide in March, beating out Instagram and TikTok. (Sarah Perez / TechCrunch)

- OpenAI may soon require organizations to verify their ID to access certain future AI models. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- OpenAI’s next breakthrough in AI models may include the capability to generate high-quality new AI ideas in research. (Stephanie Palazzolo and Amir Efrati / The Information)

- Ilya Sutskever, OpenAI cofounder, has reportedly raised $2 billion for his AI startup Safe Superintelligence, at a valuation of $32 billion. The company has yet to release a product. (George Hammond and Cristina Criddle / Financial Times)

- Alphabet and Nvidia reportedly joined others in backing SSI. (Kenrick Cai and Krystal Hu / Reuters)

- A look at how ByteDance harnessed data from its popular set of apps, including TikTok and Douyin, to grow itself into an AI powerhouse. (Meaghan Tobin / New York Times)

- Alibaba’s redesigned AI assistant Quark surpassed ByteDance’s Doubao to become China’s most popular AI app in March. (Ben Jiang / South China Morning Post)

- Google laid off hundreds of employees in its platforms and devices division, including cuts to the Android, Pixel and Chrome teams. (Erin Woo / The Information)

- Google now links to its own search results within AI Overviews. (Barry Schwartz / Search Engine Land)

- Google introduced DolphinGemma, a foundational AI model that it says can understand dolphin communications and generate responses. (Denise Herzing and Thad Starner / Google)

- YouTube introduced a new AI tool for creators to generate free instrumental tracks to use in videos so they don't have to worry about copyright violations. (Umar Shakir / The Verge)

- Apple will start analyzing data on customers’ devices to help improve its AI platform, but will not use the data directly to train AI models, the company said. (Mark Gurman / Bloomberg)

- Microsoft is finally rolling out its controversial Recall feature, which takes screenshots of users’ activity on a Copilot Plus PC, in full. (Jay Peters / The Verge)

- Netflix is testing new search technology from OpenAI that could help subscribers discover TV shows and movies and improve recommendations. (Lucas Shaw and Mark Gurman / Bloomberg)

- Adobe sparked backlash on Bluesky after making its first post there, as users defending artists made snarks about its software. The post was later deleted. (Noor Al-Sibai / Futurism)

- Hugging Face acquired French startup Pollen Robotics, the company behind the Reachy 2 robot, with plans to make it open-source. (Will Knight / Wired)

- AI reasoning models are more expensive to benchmark, new data shows, which makes companies’ claims of performance difficult to verify. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- A look at how AI can help doctors spend more quality time with patients and help assist in counseling. (Kate Pickert / Bloomberg)

Those good posts

For more good posts every day, follow Casey’s Instagram stories.

(Link)

(Link)

(Link)

Talk to us

Send us tips, comments, questions, and a: casey@platformer.news. Read our ethics policy here.