Mark Zuckerberg’s 20-year mistake

Meta’s CEO says he’s done apologizing. Should we worry?

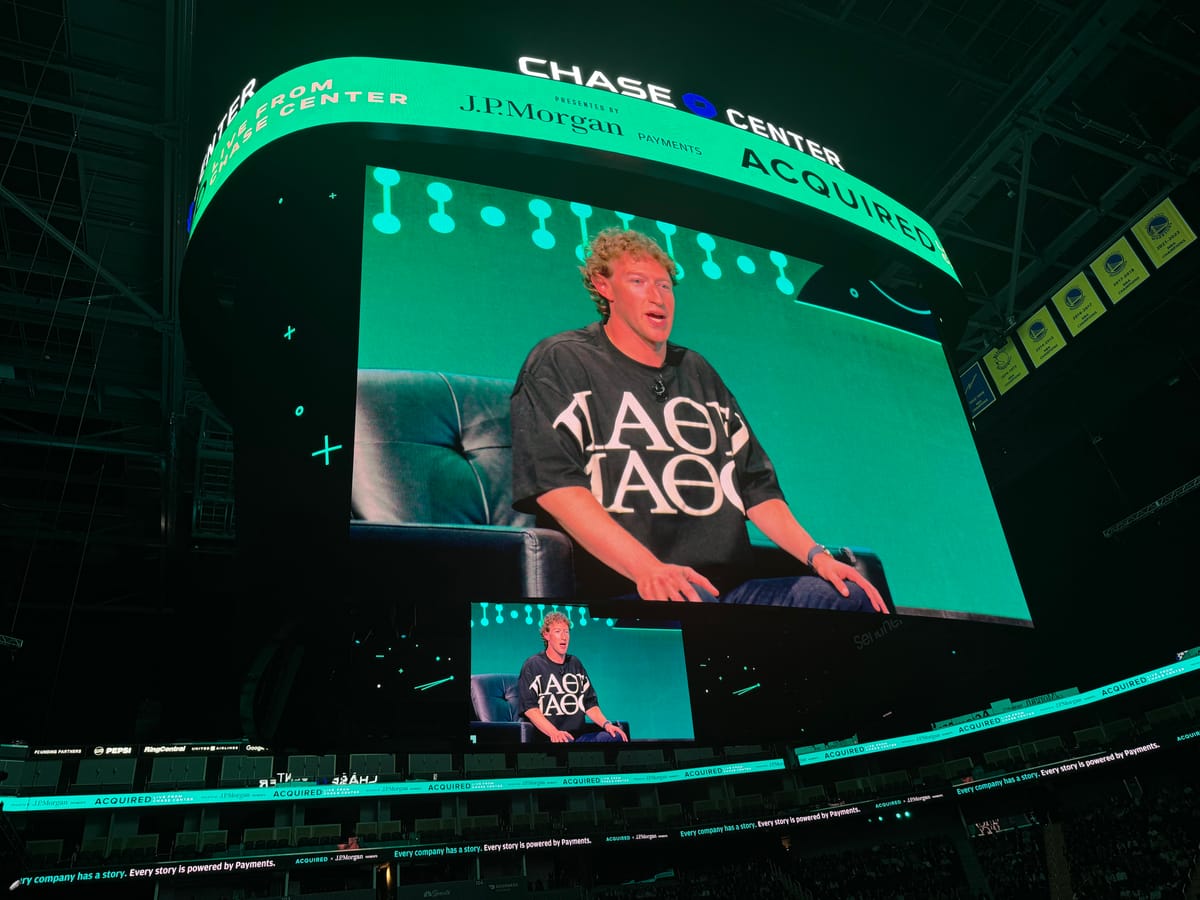

Shortly after bounding on stage Tuesday night at Chase Center, where he sat for an interview with the hosts of the Acquired podcast, Mark Zuckerberg joked that he might have to book a second appearance to apologize for what he was about to say.

It was a gentle dig at Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang, who appeared in a video shown at the event to walk back an innocuous comment he had made during his own appearance on “Acquired.” Huang said then that he never would have started the company had he known how challenging it would be; on Tuesday, he said the remark had been taken out of context.

Zuckerberg, for his part, suggested that no second appearance would be necessary. After pausing a beat, he looked out into the crowd of 6,000 or so podcast fans and said — to laughter and some applause — that he’s done apologizing.

So began one of the most revealing interviews of Zuckerberg’s career. Over more than an hour, Zuckerberg spoke with hosts Ben Gilbert and David Rosenthal about how events of the past several years have changed his perspective on leadership, politics, and product development. In most interviews with journalists since 2016, Zuckerberg quickly finds himself in a defensive crouch, working to share product announcements in between questions about platform-related harms.

In the cozier confines of Acquired, Zuckerberg seemed notably more relaxed. And that led him to do something he almost never does in public: reflect.

Zuckerberg’s reflections are of particular interest to me, since when I started writing a daily newsletter almost seven years ago, I wrote primarily about Facebook. Specifically, I wrote about Facebook in crisis: from the aftermath of the 2016 US presidential election to Cambridge Analytica and the broader backlash against tech that consumed Silicon Valley for the better part of the past decade.

Throughout those turbulent years, Zuckerberg and Facebook did apologize: for Russian interference in the election, for Cambridge Analytica, for the experiences of parents who say their children died as a result of their use of his platforms.

Talk is cheap. But those apologies were accompanied by significant investments in policy, counterterrorism, content moderation, and other efforts to shore up the integrity of the platform. The Oversight Board, an imperfect but still somewhat radical experiment in building a quasi-judicial system for a social network, also emerged from this ongoing sense of regret.

In important ways, Facebook — now Meta — escaped any real accountability for its lapses around data privacy, content moderation, and child safety. After countless performative hearings, the United States Congress did not pass a single national law to regulate Meta and other big tech companies. Meta’s user base today is bigger than it has ever been, its stock is trading near all-time highs, and Zuckerberg’s net worth is estimated by Forbes to be $182 billion. When all the world asks you for is an apology, it’s relatively easy to give.

In other ways, though, Meta continues to live in the shadow of 2016. Exasperated by the lack of action at the federal level, dozens of states are pursuing laws to make it harder for young people to access social media. The vast majority of people do not trust the company to protect their data. And the Federal Trade Commission is now suing to break up the company.

I didn’t expect any of this to come up at Acquired, a feel-good podcast about business leadership that focuses more on competitive strategy than regulatory threats. But then, about 30 minutes into the podcast taping, co-host Ben Gilbert asked Zuckerberg: “Of all the criticisms that have happened over the years, which do you believe is the most legitimate? And why?”

Zuckerberg took the opportunity to discuss his shifting calculus around the value of an apology. He had expected that publicly accepting responsibility for problems would allow the company to move on. Instead, he said, it led to critics demanding that he and Meta take responsibility for even more problems.

“I don't want to simplify this too much, and there are a lot of things that we did wrong,” he said, by a way of a caveat. And then:

One of the things that I look back on and regret is, I think we accepted other people's view of some of the things that they were asserting that we were doing wrong, or were responsible for, that I don't actually think we were. There were a lot of things that we did mess up and that we needed to fix. But I think that there's this view where, when you're a company and someone says that there's an issue, … the right instinct is to take ownership. Say, maybe it’s not all our thing, but we’re going to fully own this problem, we’re going to take responsibility, we’re going to fix it.

When it’s a political problem … Sometimes there are people who are operating in good faith, who are identifying a problem and want something to be fixed, and there are people who are just looking for someone to blame. And if your view is “I’m going to take responsibility for all this stuff” — people are basically blaming social media and the tech industry for all these things in society — if we’re saying, we’re really gonna do our part to fix this stuff, I think there were a bunch of people who just took that and were like, oh, you're taking responsibility for that? Let me like, kick you for more stuff.

He then compared the crisis to the company’s rocky initial public offering, when the company’s stock price failed to pop and prompted a wave of lawsuits around its disclosures.

“Honestly, I think we should have been firmer about and clearer about which of the things we actually felt like we had a part in and which ones we didn't. And my guess is if the IPO was a year and a half mistake, I think that the political miscalculation was a 20 year mistake. [...]

We sort of found our footing on what the principles are, and where we think we need to improve stuff. But where people make allegations about the impact of the tech industry or our company which are just not founded in any fact, that I think we should push back on harder. And I think it's going to take another 10 years or so for us to fully work through that cycle before our brand is back to the place that it maybe could have been if I hadn't messed that up in the first place.

He then turned to the audience and smiled.

“But look,” he said. “In the grand scheme of things, 20 years isn't that bad!”

What precise criticisms Zuckerberg thinks are fair, and which he thinks are made in bad faith, he did not elaborate on. You can guess, though, based on what the company actually chose to spend money on: the army of content moderators it brought on after 2017 to shore up the platform’s defenses, for example, or the Oversight Board, to which it has given $280 million so far amid complaints that Zuckerberg himself should not be the final word in difficult questions about online speech.

What he believes is unfair, I think, is the suggestion that Meta is primarily responsible for our polarized politics, the decline of democracy, or the dire state of mental health among young people in the United States.

What led Zuckerberg to lose faith in the value of contrition? Here’s a guess: ultimately, it bought him very little, at least in the court of public opinion. Meta seems equally disliked in red and blue states; this week, 42 attorneys general endorsed a plan to force Zuckerberg to add warning labels to his products saying that they put children at risk. Why apologize, you can imagine him and his lieutenants asking one another, when it gets you nowhere?

I write all of this because in a world where tech companies are very rarely held accountable in meaningful ways, it matters what CEOs do and do not feel responsible for. It matters if they decide they no longer want to take ownership of societal-level problems, even when their companies may be exacerbating them.

Almost no one thinks of the half-decade or so after 2016 as a golden age. But it was a time when Meta invested much more time, money, and talent into understanding how its products could be misused. And while surely the company would say it continues to make those investments today, it’s notable that Meta’s CEO is now signaling in public that he is turning his attention elsewhere.

Zuckerberg’s public presentation has grown notably more flamboyant in recent years; on Tuesday he wore a T-shirt he designed himself bearing the slogan “learning through suffering” in Greek letters. (“A family slogan,” he explained.)

Despite those changes, though, on Tuesday I was struck by what remains the same. Early in the conversation, he was asked about building products. Zuckerberg contrasted the company’s quick-shipping culture with Apple’s, which places a higher emphasis on polish.

“There are a lot of conversations that we have internally where you're almost at the line of being embarrassed about what you put out,” Zuckerberg said. “You want to put stuff out early enough so you can get good feedback.”

What about the damage that does to the brand, Gilbert asked.

“I would like to hope it’s not damaging to the brand,” Zuckerberg said. “We don’t ship things we think are bad. But we want to make sure we’re shipping things that are early enough that we can get good feedback to see what they’re going to be most used for.”

Facebook retired its old “move fast and break things” motto in 2014, but here it was again, in slightly updated form. It’s a slogan that explains so much of the company’s success: the way it quickly copies and improves on products from other companies, and routinely tests the boundaries of what tradeoffs people are willing to make with their privacy.

But it also explains Meta’s failures to release products that are safe, or build trust, or generate goodwill.

By his own estimation, it will take Zuckerberg another 12 years for Meta’s brand to recover from the drubbing it began to take at the end of 2016. And I can understand why he would much rather now focus on artificial intelligence, or mixed reality, or the company’s other long-term bets on the future.

But I worry about a Meta that remains just as powerful while also becoming less sensitive to public pressure and criticism. The moment Mark Zuckerberg stops apologizing could give the rest of us a lot to be sorry about.

Elsewhere in Zuckerberg: Mike Isaac looks at the changing calculus of Big Tech CEOs on where they decide to do interviews.

On the podcast this week: Kevin and I answer the question you won't stop asking: should you get the new iPhone? Then, Sapiens author Yuval Noah Harari stops by to discuss his new book and why he's grown pessimistic about AI. And finally: some recent stories about high-tech crime.

Apple | Spotify | Stitcher | Amazon | Google | YouTube

Governing

- A look at how online rhetoric, including the Springfield cat-eating anti-immigrant conspiracy, shaped Donald Trump’s performance at the presidential debate this week. (Brian Barrett / Wired)

- Right-wing media figures and influencers are using misleading and sometimes AI-generated content to push the racist conspiracy that Haitian immigrants eat cats. (Gaby Del Valle / The Verge)

- A bomb threat in Springfield, which listed two elementary schools, City Hall and a few driver’s license bureaus in Springfield prompted a major police response, officials said. Just in case anyone still thinks this stuff doesn't have real-world consequences. (Alex Presha and Armando Garcia / ABC News)

- Taylor Swift endorsed Kamala Harris after the debate, citing the AI-generated images of her suggesting that she endorsed Trump as a reason. (Mia Sato / The Verge)

- Trump Media shares plunged more than 10 percent after the debate, sinking to its lowest level since it started publicly trading as DJT. This is my favorite prediction market. (Kevin Beruninger / CNBC)

- AI leaders including Nvidia’s Jensen Huang, OpenAI’s Sam Altman and Anthropic’s Dario Amodei reportedly attended a meeting at the White House to discuss the future of AI energy infrastructure. (Hayden Field / CNBC)

- Several major AI companies have committed to take steps to combat nonconsensual deepfakes and child sexual abuse material, the White House said. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- A former publishing executive testified that it felt like they were being held hostage by Google’s ad space tool in the second day of the tech giant’s antitrust trial. (Lauren Feiner / The Verge)

- A look at residents and city officials’ clash with Elon Musk and xAI over his race to build a supercomputer in Memphis, Tenn. (Dara Kerr / NPR)

- A hacker going found a way to trick ChatGPT to ignore its guardrails and produce bomb-making instructions. An expert that reviewed the instructions said it could be used to make a detonatable product. (Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai / TechCrunch)

- Facebook is mislabeling wildfire emergency warnings by city and county officials as spam, with more than 40 instances since June. (Brianna Sacks / Washington Post)

- The FDA approved Apple’s software that powers the new hearing aid feature in the second-generation Airpods Pro. (Chris Welch / The Verge)

- SAG-AFTRA and two women’s groups, NOW and Fund Her, have sent letters to California governor Gavin Newsom to push him to sign the controversial AI safety bill. (Garrison Lovely / The Verge)

- A federal judge blocked a Utah law that would have required platforms to limit the ability for users under 18 to communicate with users not in their network, citing First Amendment concerns. (Wendy Davis / MediaPost)

- Nevada is planning to launch an AI system in partnership with Google that will analyze transcripts of unemployment hearings and issue recommendations on whether claimants should get benefits, officials say. Yikes! (Todd Feathers / Gizmodo)

- The Mental Health Coalition announced a new program, Thrive, with founding members Meta, Snap and TikTok, aimed at encouraging platforms to share signals of potentially harmful material like suicide and self-harm content. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- Ireland’s data authority is investigating whether Google’s use of personal data for AI training complies with the EU’s data laws. (Natasha Lomas / TechCrunch)

- Meta acknowledged that it scrapes public photos, posts and data of Australian adult Instagram and Facebook users to train its AI models with no opt-out option. Something else to not be sorry for! (Jake Evans / The ABC)

Industry

- OpenAI released its new reasoning model o1, previously known as Strawberry. (Kylie Robison / The Verge)

- OpenAI is reportedly in talks to raise $6.5 billion at a valuation of $150 billion, up from an $86 billion valuation earlier this year. (Rachel Metz, Edward Ludlow, Gillian Tan and Mark Bergen / Bloomberg)

- ChatGPT has surpassed 11 million paying subscribers, OpenAI COO Brad Lightcap reportedly told staff. (Amir Efrati / The Information)

- TikTok is reportedly functioning like normal internally as executives express confidence that the looming ban would be delayed. (Kaya Yurieff and Juro Osawa / The Information)

- TikTok users are developing their own ways to navigate misinformation on the app, new research suggests. (Will Oremus / Washington Post)

- Meta’s vice president of global affairs Nick Clegg said Elon Musk had turned X into “a sort of one man, sort of hyper-partisan and ideological hobby horse” by not moderating it well. (Vincent Manancourt / Politico)

- A test of whether Threads can be manipulated to promote engagement baiting. Katie is almost single-handedly making Threads a joy to use. (Katie Notopoulos / Business Insider)

- WhatsApp is letting small businesses in India sign up for a Meta Verified badge and allowing them to send customized messages. (Jagmeet Singh and Ivan Mehta / TechCrunch)

- Meta is updating its AI labels on Instagram, Facebook and Threads to move it to a menu in the top-right corner of posts instead of directly under a user’s name. (Jess Weatherbed and Emma Roth / The Verge)

- Google’s AI note-taking app, NotebookLM, can now generate an AI podcast complete with two “hosts” that banter from the research and documents in it. (Emma Roth / The Verge)

- Google co-founder Sergey Brin says he’s back working regularly at the company on AI projects. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- Results on Google Search will now link directly to the Internet Archive for historical context. (Ben Schoon / 9to5Google)

- A look inside Google’s AI-powered robotics moonshot project as told by the head of the department. (Hans Peter Brondmo / Wired)

- Gemini Live is beginning its rollout to free Android users after its initial rollout to Advanced subscribers a month ago. (Abner Li / 9to5Google)

- Google unlisted a Gemini demo video after an ad industry watchdog inquired about whether the video “accurately depicts the performance of Gemini in responding to user voice and video prompts.” (Jay Peters / The Verge)

- Apple Intelligence’s cloud services have infrastructure that protects privacy called Private Cloud Compute, the company says, which allows data to be “hermetically sealed inside of a privacy bubble.” (Lily Hay Newman / Wired)

- Microsoft hired Carolina Dybeck Happe, previously GE’s senior vice president and chief financial officer, as its executive vice president and chief operations officer. (David Faber and Jordan Novet / CNBC)

- Microsoft is planning to change Windows to allow security vendors like Crowdstrike to operate outside of the Windows kernel to prevent another incident. (Tom Warren / The Verge)

- Bluesky users can now post videos up to 60 seconds long on the platform. (Emma Roth / The Verge)

- The app is now nearing 10 million users due to X’s brazil ban. (Sarah Perez / TechCrunch)

- Cohost, which launched in June 2022 as an X alternative with a chronological feed, is shutting down. (Sarah Perez / TechCrunch)

- Spotify is reportedly offering video creators up to seven figures to distribute content on the platform in addition to YouTube. (Ashley Carman / Bloomberg)

- AI features powered by the Firefly Video model will be available on the Premier Pro beta app and a free website by the end of the year, Adobe announced. (Maxwell Zeff / TechCrunch)

- A look at how a local newspaper in Hawaii started using AI-generated presenters in place of reporters. (Guthrie Scrimgeour / Wired)

Those good posts

For more good posts every day, follow Casey’s Instagram stories.

(Link)

(Link)

(Link)

Talk to us

Send us tips, comments, questions, and apologies: casey@platformer.news and zoe@platformer.news.