The AI agents have arrived

Artificial intelligence can now compute for you on your behalf — and the web is never going to be the same

Earlier this year, in a much-discussed tagline from its annual developer event, Google promised that its AI-enhanced search engine would soon do the Googling for you.

Five months later, an even more expansive future is coming into view: one where your computer does the computing for you.

That’s the promise contained within Claude 3.5 Sonnet, the latest version of Anthropic’s flagship large language model. Starting today, developers have access to a feature called “computer use.” The company describes it this way:

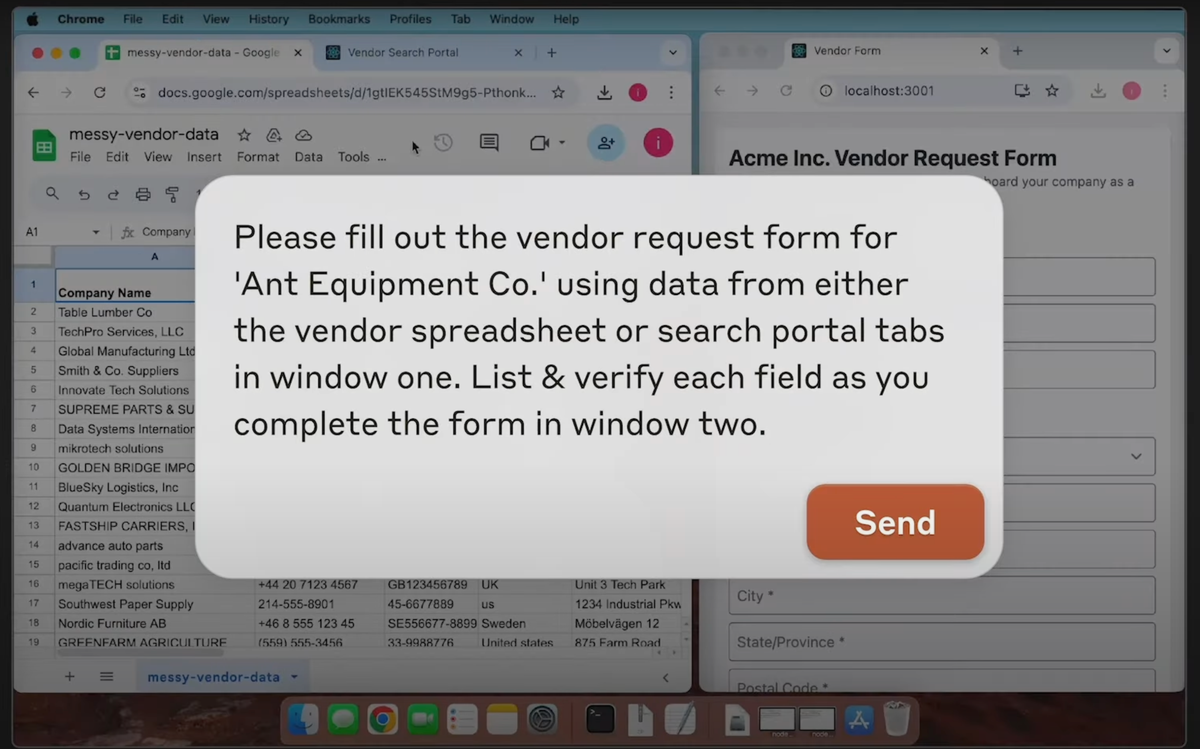

Available today on the API, developers can direct Claude to use computers the way people do—by looking at a screen, moving a cursor, clicking buttons, and typing text. Claude 3.5 Sonnet is the first frontier AI model to offer computer use in public beta. At this stage, it is still experimental — at times cumbersome and error-prone. We're releasing computer use early for feedback from developers, and expect the capability to improve rapidly over time.

A brief accompanying video shows an Anthropic researcher using its agent to gather information from various places on his computer and using it to fill out a form. It’s a mundane example, but that’s the point: building an AI agent smart enough to automate the drudgery that fills so many workers’ days.

Anthropic is quick to note that this first version of the technology is slow and makes lots of mistakes. But it also heralds the arrival of the next major phase on the AI labs’ road to building superintelligence.

Anthropic is only one of dozens of companies now working to build AI agents. Microsoft today announced 10 new automations for its Dynamics 365 suite of business applications. Asana rolled out a take on agents today as well. Salesforce’s rival Agentforce technology is due to become generally available next week. And a host of startups are racing to build “AI co-workers” of various kinds.

What makes Anthropic’s agent stand out is that it takes the same technology that powers the AI chatbots we have been using for almost two years now and lets it out of the text box. Instead of being limited to offering you text- or voice-based responses, it can now complete small projects on your behalf.

Ethan Mollick, an associate professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, got a chance to try Anthropic’s agent early. He had it whip up a lesson plan for him while he did other things:

As one example, I asked the AI to put together a lesson plan on the Great Gatsby for high school students, breaking it into readable chunks and then creating assignments and connections tied to the Common Core learning standard. I also asked it to put this all into a single spreadsheet for me. With a chatbot, I would have needed to direct the AI through each step, using it as a co-intelligence to develop a plan together. This was different. Once given the instructions, the AI went through the steps itself: it downloaded the book, it looked up lesson plans on the web, it opened a spreadsheet application and filled out an initial lesson plan, then it looked up Common Core standards, added revisions to the spreadsheet, and so on for multiple steps. The results are not bad (I checked and did not see obvious errors, but there may be some — more on reliability later in the post). Most importantly, I was presented finished drafts to comment on, not a process to manage. I simply delegated a complex task and walked away from my computer, checking back later to see what it did (the system is quite slow).

Later, he used it to play the game Paperclip Clicker (“which, ironically, is about an AI that destroys humanity in its single-minded pursuit of making paperclips.”) It fares poorly — making one mistake leads it to make many more, forcing Mollick to intervene. Overall, he writes, the agent could handle a variety of tasks with some success, though not enough that he would feel comfortable routinely delegating work to it.

This will surely lead to many comical TikToks of Claude trying and failing to demonstrate basic computer skills. But I was struck by the company’s blog post on developing the agent, which notes that even at this most experimental stage, Claude is twice as good at navigating as its next-closest competitor — and maybe not as far from human-level performance as you might guess:

At present, Claude is state-of-the-art for models that use computers in the same way as a person does — that is, from looking at the screen and taking actions in response. On one evaluation created to test developers’ attempts to have models use computers, OSWorld, Claude currently gets 14.9%. That’s nowhere near human-level skill (which is generally 70-75%), but it’s far higher than the 7.7% obtained by the next-best AI model in the same category.

To be clear, a grade of 14.9 percent is an F by most measures. But on this test, most humans only score a C. It’s a welcome reminder of how much trouble most of us have navigating computer-based tasks at least some of the time — and an important milestone on the way to agents that can make those troubles go away.

And what happens then?

It’s easy to imagine using an AI agent to manage your appointments and scheduling, fill out online forms and routine paperwork, draft replies to your emails, and shopping on your behalf. Or it could browse the web on your behalf, preparing a personalized digest for you that means you never have to fight against a paywall ever again.

It’s also easy to imagine an agent with those capabilities setting up spam operations, automating the production of AI slop websites, and overwhelming human-run businesses and institutions with a flood of AI-generated requests.

Either way, people who use AI agents will have to confront some very real privacy concerns. Earlier this year Microsoft had to delay the launch of Recall, a marquee feature in its new AI-centric PCs designed to let you search all past activity on the computer via AI-powered search of screenshots that it silently takes in the background for you. Security researchers pointed out, among other things, that users would be opted in by default, and that their screenshots were not encrypted, creating an appealing target for hackers. (Users now have to opt in, and the screenshots are encrypted.)

Anthropic will need similar access to a user’s computer to operate it on their behalf. And I imagine businesses will have many questions about what the company does with customer data, and with employee data, before letting anyone use it.

There also may still be real limits in how much we can expect from agents in the near term. One startup CEO ridiculed to me the idea, popular in AI circles, that “the next major programming language is English.” (In other words, the idea that you’ll soon be able to get software to do whatever you want it to do simply by saying so.) CEOs “program in English” all the time, he explained, by telling their human engineers what to build. And that process is famously error-prone and rife with inefficiency, too.

But to use another phrase popular among the AI crowd, the agent that Anthropic released today is as bad as this kind of software will ever be. From this moment on, AI will no longer be limited to what can be typed inside a box. Which means it’s time for the rest of us to start thinking outside that box, too.

Sponsored

Height.app—The only autonomous project management tool

Height is rewriting the project management playbook. Leading the next wave of AI tooling for product teams, Height proactively handles all of the tedious tagging, triaging, and updating, so you never have to again. Height autonomously takes care of product workflows like:

- Detecting scope changes and mapping edits back to your specs

- Triaging bugs, assigning priority and escalating as needed

- Tagging and organizing backlogs by feature, estimate, and more

If you're tired of managing projects, it's time for Height. Join the new era of product building — where projects manage themselves.

Elon Musk and the 2024 election

This absolutely could have been the subject of today's column. But I couldn't imagine telling you anything I haven't already said on the subject over and over again. Musk's attempted vote-buying scheme represents an extraordinary departure for big company CEOs, and may well be illegal. Had Mark Zuckerberg tried anything like this in 2020, Rep. Jim Jordan would have ordered airstrikes on Menlo Park.

(If you think I should have written this column instead today, I'd be curious to hear about it. Just reply to this email.)

- Prosecutors are facing mounting pressure to investigate Elon Musk’s $1 million daily lottery that he promised to voters that signed his PAC’s petition. (David Ingram, Ken Dilanian, Michael Kosnar, Fallon Gallagher and Lora Kolodny / NBC News)

- Former Republican lawmakers and officials have reportedly sent a letter to attorney general Merrick Garland urging him to investigate Musk for the move. (Perry Stein / Washington Post)

- Pennsylvania governor Josh Shapiro also said Musk's move was something “law enforcement can take a look at.” (Colby Smith / Financial Times)

- The daily lottery could violate election bribery laws, experts say. (Marshall Cohen / CNN)

- The PAC funded by Musk is reportedly struggling to meet doorknocking goals and investigating claims that workers lied about the number of voters contacted. (Rachael Levy and Alexandra Ulmer / Reuters)

- The PAC has spent more than $166,000 on advertising on X. So at least someone is advertising on X! (Vittoria Elliott / Wired)

- A look at how entangled Musk is with several federal agencies, and how a Trump presidency could give him more power over them. A story that perhaps explains what is going on here better than any other. (Eric Lipton, David A. Fahrenthold, Aaron Krolik and Kirsten Grind / New York Times)

- Musk shared a post on X falsely claiming that Michigan’s voter rolls had a large number of inactive voters and could lead to widespread fraud. Michigan secretary of state Jocelyn Benson said the post was “dangerous disinformation.” It is also part of the Republican effort to delegitimize the election before it even takes place. (Sarah Ellison / Washington Post)

- A look at the different ways Musk has spread conspiracy theories and misinformation about the election online. (Julia Ingram and Madeleine May / CBS News)

Governing

- Bill Gates has reportedly said privately that he made a $50 million donation to an organization backing Kamala Harris’ campaign. (Theodore Schleifer / New York Times)

- A look inside Harris’ campaign and its efforts to win back support from tech industry leaders who soured on Biden. (Cat Zakrzewski, Nitasha Tiku and Elizabeth Dwoskin / Washington Post)

- Shares of Trump Media have soared despite reported internal complaints from employees accusing executives of an over-reliance on foreign contract workers and mismanagement. (Matthew Goldstein / New York Times)

- Social media platforms – facing legal warfare from Republicans – have pulled back from moderating election misinformation. A dispiriting and successful case of working the refs. (Brian Fung / CNN)

- Russia and Iran might attempt to stoke election-related protests and violent actions in the US on and after election day, US intelligence officials warn. (Dustin Volz / Wall Street Journal)

- Accounts tracking the private jets of celebrities like Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk and Bill Gates were suspended on Instagram and Threads yesterday. A strange move given that flight data for private jets is public information. (Maxwell Zeff / TechCrunch)

- A look at how the 2024 election is playing out on TikTok. (Sapna Maheshwari and Madison Malone Kircher / New York Times)

- Amazon, in response to a National Labor Relations Board complaint, reportedly said its union-busting tactics, such as holding captive-audience meetings, are protected by the First Amendment. (Jules Roscoe / 404 Media)

- Advocacy groups are urging the California Bar to investigate Kent Walker, Google’s president of global affairs, for allegedly “coaching” the company to destroy records relevant to antitrust trials. (Lauren Feiner / The Verge)

- Widespread surveillance by Flock, a company that sells automated license plate readers, is unconstitutional and violates the Fourth Amendment, a new lawsuit in Virginia alleges. (Jason Koebler / 404 Media)

- Ireland adopted an Online Safety Code with content moderation requirements that will apply to video platforms headquartered in the country, including TikTok, YouTube, Instagram and Facebook Reels. (Natasha Lomas / TechCrunch)

- Twitch temporarily blocked users from Israel and Palestine from creating new accounts following Oct. 7 to “prevent uploads of graphic material” of the attack and for safety, the company said. Geo-blocking account creation is a common (if brute-force) trust and safety tactic, but it's extraordinary that Twitch blocked it for this long. (Emanuel Maiberg / 404 Media)

Industry

- OpenAI and Microsoft are funding a $10 million AI collaborative and fellowship program for five metro news organizations, operated by the journalism nonprofit Lenfest Institute. (Sara Fischer / Axios)

- OpenAI’s first chief economist is Aaron Chatterji, former chief economist at the Commerce Department and former senior economist in Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers. (Kyle Wiggers / TechCrunch)

- OpenAI also hired Scott Schools, formerly Uber’s chief ethics and compliance officer, as its first chief compliance officer. (Shirin Ghaffary / Bloomberg)

- AI startup Perplexity is reportedly in talks for a $500 million funding round that would double its valuation to $8 billion or more. (Berber Jin and Tom Dotan / Wall Street Journal)

- ByteDance fired an intern for “maliciously interfering” with the training of one of its AI models. (João da Silva / BBC)

- The Meta Ray-Ban smart glasses are the top selling product in 60 percent of Ray-Ban stores in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, Ray-Ban parent EssilorLuxottica said. (David Heaney / UploadVR)

- Meta is expanding testing for facial recognition as part of its ad review system in an effort to combat celebrity scam ads. A fraught return to facial recognition from a company that loudly abandoned the practice years ago; it may be worth it if (as promised) it can actually help people whose accounts get stolen recover them. (Natasha Lomas / TechCrunch)

- WhatsApp will allow users to store contacts within the app. (Ivan Mehta / TechCrunch)

- A Q&A with Google DeepMind’s Demis Hassabis right after he won a Nobel Prize and what he thinks AI could do for science. (Madhumita Murgia / Financial Times)

- Gen Z AI messaging app Daze is already seeing more than 150,000 signups on its pre-launch waitlist. It looks fun and I would like to try it! (Sarah Perez / TechCrunch)

- The Foursquare City Guide app is shutting down, founder Dennis Crowley said, as the company focuses on its Swarm check-in app instead. A sad day for a once-great social app. (Sarah Perez / TechCrunch)

- A statement signed by 10,500 people in creative industries, including actress Julianne Moore and Radiohead singer Thom Yorke, is warning AI companies that unlicensed use of their work is a “major, unjust threat” to their livelihoods. (Dan Milmo / The Guardian)

- AI detectors used in schools are falsely flagging students’ work as plagiarism and could cause devastating consequences, students say. (Jackie Davalos and Leon Yin / Bloomberg)

- A look at the different ways personality is being added into AI chatbots through training. (Cristina Criddle / Financial Times)

Those good posts

For more good posts every day, follow Casey’s Instagram stories.

(Link)

(Link)

(Link)

Talk to us

Send us tips, comments, questions, and tasks for your AI agent: casey@platformer.news.