How CrowdTangle predicted the future

Meta is killing off a pioneering tool for platform transparency — but the movement it kickstarted is just beginning

Eight years after buying the data analysis tool CrowdTangle, and four years after it began exasperating the executives responsible for it, Meta said Thursday that it would shut down the tool on August 14.

CrowdTangle, a data analysis tool that allowed researchers, journalists, and other members of civil society to understand the spread of content on Meta’s platforms, was never among the company’s most popular products. But it was perhaps the first major tool offered by a big social network to let the public analyze trends on the platform in real time.

With CrowdTangle now set to disappear — just 12 weeks before the US presidential election — Meta is encouraging researchers to instead use its Meta Content Library. But while the content library improves on CrowdTangle in some key ways, it’s also much less broadly available than its predecessor was.

The question now is whether the visibility that CrowdTangle once brought to Facebook can be preserved and expanded at Meta and other platforms — or whether, given all the unwelcome scrutiny it brought, platforms will work to avoid the real-time transparency it offered.

I. The history

CrowdTangle was founded in 2012 by Brandon Silverman and Matt Garmur. Their original idea had been to build tools for online activists on Facebook. When that didn’t work out, they turned their attention to building tools for publishers. Their first successful product was a dashboard that showed you which posts on Facebook pages were getting the most engagement.

It was the right tool at the right time. Facebook was then arguably the most important company in journalism, funneling millions of pageviews to a wide array of digital publishers. By using CrowdTangle, publishers could understand what worked on the platform instantly, and could adjust their output accordingly.

This did not necessarily lead to better journalism. Instead, it led to a kind of spreading sameness around the web, as publishers began using CrowdTangle dashboards to identify their competitors’ posts and quickly fire off their own versions. (If you wonder why every single publisher posted Game of Thrones trailers in the 2010s, no matter what their websites were nominally about, CrowdTangle is a big reason why.)

In November 2016 — days after Donald Trump had won the presidency — Facebook bought CrowdTangle for an undisclosed sum. The move came arguably at the peak of Facebook’s interest in journalism. Days earlier, damning stories about the platform’s promotion of election misinformation began to batter the company, sparking a yearslong backlash that only recently has begun to wane. Facebook began to reduce the distribution of news in its apps, kicking off a long divorce that culminated recently in the announcement last month that the company would deprecate its news tab in the United States and elsewhere and would no longer make commercial deals with publishers.

Along the way, though, CrowdTangle had come to serve a very different purpose than its founders had originally intended. It turned out that a tool that shows which stories are spreading most quickly on the platform is useful for more than just seeing which low-effort stories to copy. It’s also useful for researchers and journalists tracking the spread of false narratives and other potentially harmful content.

In 2020, New York Times columnist Kevin Roose used CrowdTangle data to create a bot that each day tweeted the stories getting the most engagement on public pages in the United States. (Roose is my friend and we now co-host the Hard Fork podcast together.) The bot found that, contrary to the then-popular narrative among conservatives that Facebook worked to suppress their reach, the most popular posts on the platform were often right-leaning.

Facebook executives hated this bot. Advertisers and policymakers were calling them up asking about Roose’s tweets. Executives tried to explain that the bot measured only engagement. The fairer way to measure the spread of content on Facebook, they said, is reach: how many people view a post, rather than how many share or comment on it. When you measure by reach, executives said, the news posts that most people on Facebook see are much more centrist.

That might be true, but Facebook did not regularly make that data public. In any case, it put Facebook in the difficult position of telling journalists and policymakers to ignore the data generated by its own tool. Suddenly, CrowdTangle had become perhaps the weirdest product in Facebook’s history: beloved by its users, disavowed by its owners.

Something had to give. And indeed, in the summer of 2021, Meta dissolved the team that ran CrowdTangle. The following year, it stopped accepting new users.

"CrowdTangle’s only sin was being too useful," Roose told me today. "Without journalists having access to this data, the public will have a poorer understanding of what happens on Meta’s platforms — which is exactly why Meta executives decided to kill it."

II. The library

Meta might have simply shut down CrowdTangle in 2022, had it not been for a regulatory wrinkle: the European Union’s Digital Services Act. Article 40 of the act requires very large platforms and search engines to share publicly available data with researchers and nonprofit groups, so long as it contributes to “the detection, identification and understanding of systemic risks in the Union.”

Meta is considered a very large platform under the DSA. And in November it unveiled the Meta Content Library, which is designed to fulfill its obligations under European law.

Nick Clegg, Meta’s president of global affairs, said in an interview this week that the Meta Content Library is a better tool for researchers than CrowdTangle in almost every way. For starters, it includes data about reach, which he said offers a better picture of what content on the platform is most popular. It also includes access to types of content that were never available in CrowdTangle, including comments and the Reels short-form video format.

“Of course I understand that people who are wedded to the use of that tool will maybe shed a tear that it's been deprecated,” Clegg said. “But it's being more than replaced, actually. It's being entirely outpaced by the new tools that we're making available: the Meta Content Library — the UI and the API — which is just a much, much more robust and much more sophisticated tool to do what I think people reasonably expect us to do, which is to allow researchers to really … lift the hood and really look into the bowels of our system.”

Access to the library is governed by the independent Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research at the University of Michigan (ICPSR). At the moment, the number of researchers with access to the library is in the hundreds. But Clegg said he hopes that figure grows considerably over time. By the end of this month, he said, Meta hopes to have 1,000 fact-checkers using the library.

At the same time, aside from fact checkers, journalists won’t have direct access to the library. If they want to perform analysis on Facebook data in the future, they’ll need to partner with a nonprofit group or research group that does have it.

CrowdTangle founder Silverman told me that it is likely more important that civil society have access to real-time platform data than academic researchers. The reason, he said, is that academic research takes so long. Meta granted some researchers access to data related to the 2020 US presidential election for study; the first papers on the subject weren’t published until July 2023.

“The main value of systems like this is providing a kind of observability function for civil society,” Silverman said in an interview. “The academic stuff is just too slow.”

III. The future

The risk of Meta’s approach to transparency with the library is that while the data is much better, access to it is much more limited, and any insights to be gotten from it will take much longer to arrive. That would blunt the benefit of any improvements within the library itself, Silverman said.

Meanwhile, researchers who have used both CrowdTangle and the content library say that they have different strengths and weaknesses.

Naomi Shiffman, head of data and implementation at the Oversight Board, told me that the library “has the potential to be better than CrowdTangle” over time. That’s important for the board, Meta’s independent, quasi-judicial branch, which has the final word on what posts stay up or come down and which advises it on policy matters. When Meta won’t give the board the data it requests, it often uses CrowdTangle as a last resort, as we reported last month.

Still, she said, “there are areas where CrowdTangle is still significantly better – Instagram coverage is currently more comprehensive in CrowdTangle than the content library, and CrowdTangle lets you search phrases, not just individual keywords.”

CrowdTangle also helps the board understand how quickly a post is going viral by showing how much engagement it gets in 15-minute increments. That lets researchers compare posts by how quickly they spread as opposed to their total engagement, she said.

“We’ve heard their team is working on improving Instagram coverage and incorporating phrase search as a product feature, but until that happens, it will be a challenge to pull the right data while operating within the limits of the tool,” Shiffman said.

Despite those challenges, Silverman told me that he remains optimistic about the future of platform transparency. Before the DSA, we had to rely on companies volunteering to give researchers access. Today, they must do so by law. The result is that researchers now have a legal right to request data from platforms that have never offered it before, including Google, YouTube, LinkedIn, and Snapchat.

“What we really wanted was also transparency across the entire industry,” Silverman said. “I just don’t think we can rely on volunteer efforts in this space.”

It might have been nice to live in a world where both CrowdTangle and the content library, with their various strengths and weaknesses, were available. But Silverman said he was content knowing that the idea CrowdTangle came to stand for — that there should be some level of public access to these private repositories of speech — had since been enshrined into law.

“In the end, it’s a trade I’m actually happy with,” he said.

Correction, 3/15: This post originally said there were about 100 researchers using the Meta content library. The number is actually several hundred.

More on CrowdTangle: Silverman offers more thoughts on the service on his Substack.

How to apply to for research access to very large online platforms under the DSA: Just follow the instructions at these links!

- Meta Content Library

- X/Twitter

- Alibaba

- TikTok Research API

- Alphabet (YouTube, Maps, Play, Search, Shopping)

- Snapchat

- Booking.com

- AliExpress

- Bing

Sponsored

Investors are focused on these metrics.

Startups should take notice.

It takes more than a great idea to make your ambitions real. That’s why Mercury goes beyond banking* to share the knowledge and network startups need to succeed. In this article, they shed light on the key metrics investors have their sights set on right now.

Even in today’s challenging market, investments in early-stage startups are still being made. That’s because VCs and investors haven’t stopped looking for opportunities — they’ve simply shifted what they are searching for. By understanding investors’ key metrics, early-stage startups can laser-focus their next investor pitch to land the funding necessary to take their company to the next stage.

Read the full article to learn how investors think and how you can lean into these numbers today.

*Mercury is a financial technology company, not a bank. Banking services provided by Choice Financial Group and Evolve Bank & Trust®; Members FDIC.

On the podcast this week: Kevin and I talk through the politics of a TikTok ban. Then, a critique of Kate Middleton's Photoshop skills. And finally, the Times' Kashmir Hill joins us to discuss how our cars started snitching on us.

Apple | Spotify | Stitcher | Amazon | Google | YouTube

TikTok

- The House voted to pass the bill that could force a TikTok sale to a US entity, or face a ban. (Cristiano Lima-Strong, Jacob Bogage and Mariana Alfaro / Washington Post)

- While the TikTok bill sped through the House, its fate in the Senate is uncertain. (Drew Harwell, Cristiano Lima-Strong, Ellen Nakashima and Jacob Bogage / Washington Post)

- The Senate is expected to weigh the wider implications a ban could cause. (Andrew Ross Sorkin, Ravi Mattu, Bernhard Warner, Sarah Kessler, Michael J. de la Merced, Lauren Hirsch and Ephrat Livni / New York Times)

- TikTok reportedly told employees that its strategy to protect user data is not going to change. (Edward Ludlow and Alex Barinka / Bloomberg)

- TikTok executives reportedly told their bosses in Singapore that they weren’t in danger of being banned, just two weeks ago. (Stu Woo, Georgia Wells and Raffaele Huang / Wall Street Journal)

- If the bill becomes law, it would likely spark legal battles questioning the constitutionality of the government’s efforts. (Drew Harwell and Eva Dou / Washington Post)

- China is calling on Congress to “stop unfairly suppressing foreign companies.” Meanwhile, Steven Mnuchin said he’s putting together an investment group to buy the app. (Eleanor Olcott / Financial Times)

- The growing threat of the ban is also spotlighting an open secret – that the app loses money. (Jing Yang, Kate Clark and Erin Woo / The Information)

- According to a report funded by TikTok, the company drove $14.7 billion in small business owners’ revenue last year, and supports at least 224,000 jobs in the US. (Taylor Lorenz / Washington Post)

- Creators are concerned about their livelihoods on TikTok if a ban comes to fruition. (Sara Ashley O’Brien, Ashley Wong and Lindsey Choo / Wall Street Journal)

- TikTok is expanding its Effect Creator Rewards program to more countries and lowering the amount of videos creators need to use an effect in to get a payout. Cash those checks while you can! (Aisha Malik / TechCrunch)

- TikTok was fined almost $11 million in Italy after an investigation into safety concerns following the “French scar” challenge. Oh sure, kick them while they're down! (Natasha Lomas / TechCrunch)

Governing

- The EU approved the AI Act, the first in the world to set wide-ranging regulatory ground rules for AI. (Karen Gilchrist and Ruxandra Iordache / CNBC)

- The SEC is accusing Elon Musk of trying to stall its investigation through “baseless constitutional objections” against testifying. (Jess Weatherbed / The Verge)

- X took down a video of purported cannibalism posted by Musk for violating the platform’s rules. It takes a lot for a Musk story to shock me, but this one did. (Craig Trudell / Bloomberg)

- Midjourney has started blocking users from generating images of Biden and Trump ahead of the election, tests show. (Matt O’Brien / Associated Press)

- Trump reportedly authorized the CIA in 2019 to launch a campaign on Chinese social media aimed at turning the Chinese public against its government. (Joel Schectman and Christopher Bing / Reuters)

- The New York Times says OpenAI’s claim that the newspaper “hacked” its AI systems is “irrelevant as it is false.” (Blake Brittain / Reuters)

- Pornhub, along with other sites that are part of parent Aylo, blocked access to its site in Texas over age verification requirements. (Samantha Cole / 404 Media)

- A sprawling international ecosystem of predators is using platforms like Discord and Minecraft to exploit and harm children. (Ali Winston / WIRED)

- These groups often coerce children into degrading and violent acts, including self-harm. (Shawn Boburg, Pranshu Verma and Chris Dehghanpoor / Washington Post)

How growing up in a world of smartphones negatively impacts human development. (Jonathan Haidt / The Atlantic)

Industry

- Don Lemon said Elon Musk canceled his show on X hours after he did a tense interview with the executive. (Alex Weprin / The Hollywood Reporter)

- Google paid out about $10 million to 632 researchers last year for finding and reporting security flaws in its products and services. (Bill Toulas / Bleeping Computer)

- Google’s new Search Generative Experience could cost publishers over 60 percent of their organic traffic, according to this analysis. (Trishla Ostwal / Adweek)

- Chrome now has real-time browsing protection, which Google says hides visited URLs. (Sheena Vasani / The Verge)

- DeepMind unveiled SIMA, an AI agent that learns how to play games like a human. (Emilia David / The Verge)

- YouTube is redesigning its TV app to make shopping easier. (Chris Welch / The Verge)

- Meta’s former head of Oculus (and a longtime Google executive before that) offers his thoughts on the Vision Pro. (Hugo Barra / Hugo’s Blog)

- Apple quietly bought Canadian AI startup DarwinAI. (Mark Gurman / Bloomberg)

- An interview with OpenAI CTO Mira Murati, on Sora and its roll-out plan. (Joanna Stern / Wall Street Journal)

- OpenAI struck licensing deals with two major European publishers, French paper Le Monde and Spanish conglomerate Prisa. (Shirin Ghaffary / Bloomberg)

- Amazon will soon let sellers make product pages just by copy and pasting a link, with a new AI tool. (Emilia David / The Verge)

- After charging merchants to promote products shoppers can’t buy, Amazon is pledging to fix its mistakes. (Spencer Soper / Bloomberg)

- Neil Young is putting his music back on Spotify, noting that Apple and Amazon have also started hosting the Joe Rogan podcast that Young says spreads vaccine disinformation. (Chris Eggertsen / Billboard)

- Spotify is adding music videos in beta in some countries – the US isn’t one of them. (Romain Dillet / TechCrunch)

- Spotify is accusing Apple of stonewalling an update to its app that shows pricing information in the EU. (Emma Roth / The Verge)

- Snapchat will now allow users to save DMs between friends, a feature called “Infinite Retention Mode.” (Sara Fischer / Axios)

- A look at Reddit’s long, rocky path to its IPO. (Mike Isaac / New York Times)

- Bluesky launched open-sourced Ozone, a tool for content moderation that lets users review and label content on the network. (Aisha Malik / TechCrunch)

- BeReal is reportedly considering raising a Series C round or acquisition, as growth stalls. (Kali Hays and Callum Burroughs / Business Insider)

- Brave, the privacy-focused browser, has seen a sharp increase in installs after Apple’s DMA browser changes in the EU. (Mayank Parmar / Bleeping Computer)

- Tim Berners-Lee’s open letter on the world wide web’s 35th birthday. He's worried about consolidation of power. (Tim Berners-Lee / World Wide Web Foundation)

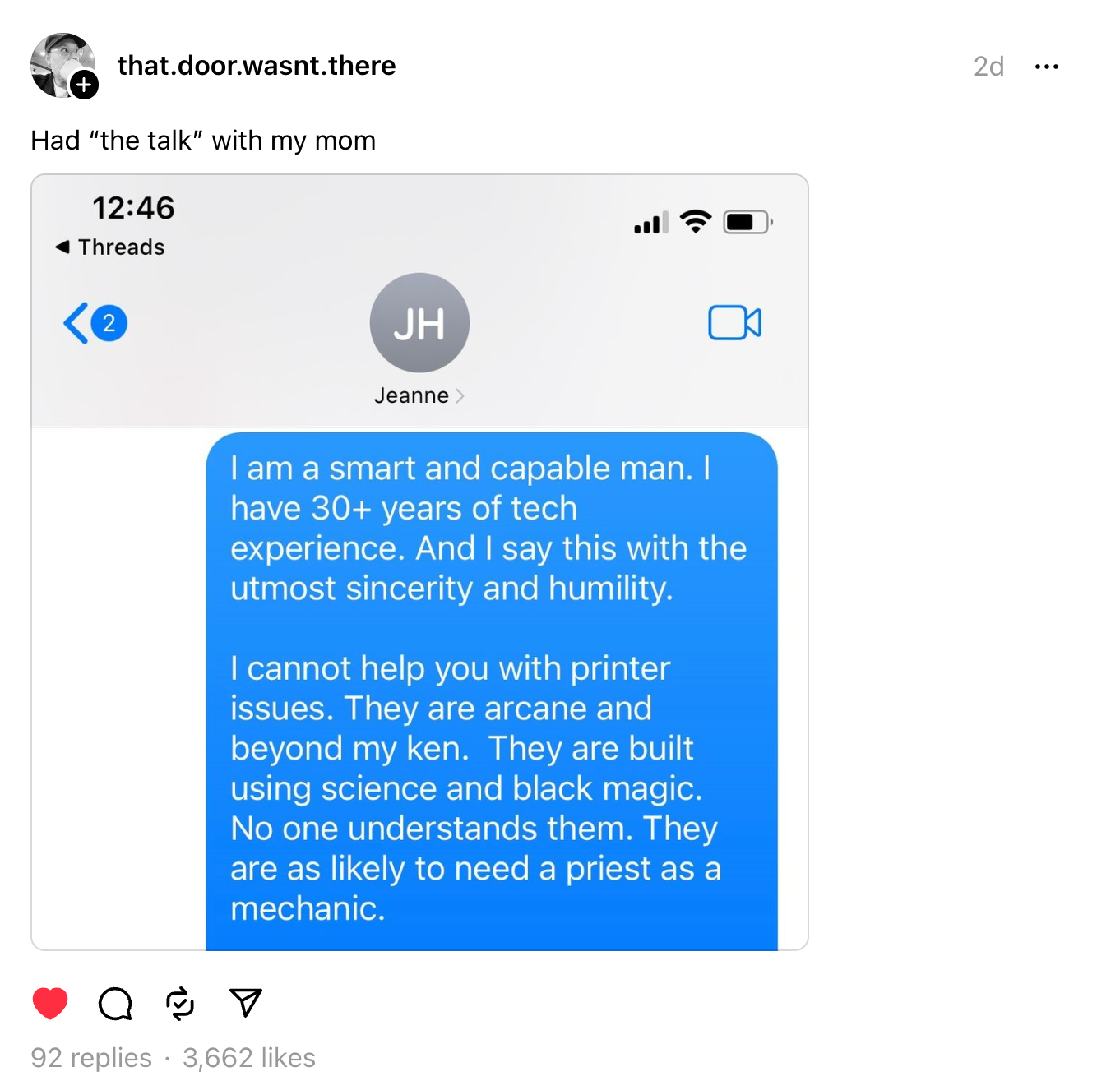

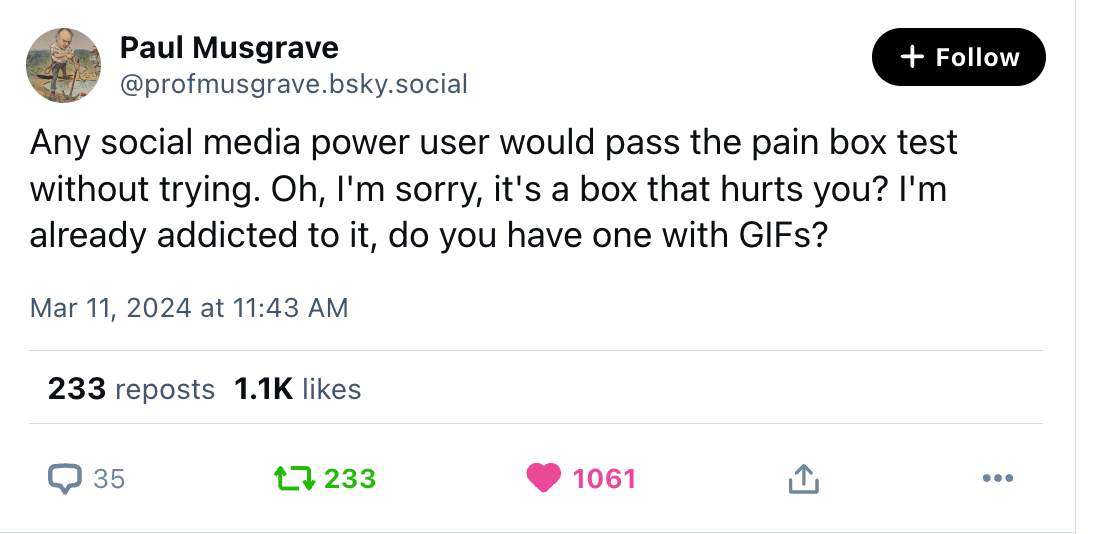

Those good posts

For more good posts every day, follow Casey’s Instagram stories.

(Link)

(Link)

(Link)

Talk to us

Send us tips, comments, questions, and old CrowdTangle dashboards: casey@platformer.news and zoe@platformer.news.