The Department of Justice comes for Apple

One way or another, real competition may be coming to the iPhone

Today let’s talk about one of the most significant antitrust lawsuits ever filed in the tech industry: this 88-page complaint against Apple, filed by the Department of Justice and joined by 16 states, accusing the iPhone maker of illegally maintaining its monopoly over high-end smartphones and artificially inflating prices for consumers.

Here are Dave Michaels and Aaron Tilley in the Wall Street Journal:

The government’s antitrust complaint, filed in a New Jersey federal court, alleges Apple used its control of the iPhone to prevent competitors from offering innovative services such as digital wallets and limited the functionality of hardware products that compete with Apple’s own devices. The suit also claims that Apple makes it difficult for users to switch to devices that don’t use Apple’s operating system, such as Android smartphones.

Apple “has maintained its power, not because of its superiority, but because of its unlawful exclusionary behavior,” Attorney General Merrick Garland said at a press event.

Apple responded by saying that the lawsuit represents a case of government overreach:

This lawsuit threatens who we are and the principles that set Apple products apart in fiercely competitive markets. If successful, it would hinder our ability to create the kind of technology people expect from Apple — where hardware, software, and services intersect. It would also set a dangerous precedent, empowering government to take a heavy hand in designing people's technology. We believe this lawsuit is wrong on the facts and the law, and we will vigorously defend against it.

I. The market, defined

The first question to ask with any antitrust case is how regulators are defining the relevant market. In order to prove that a company is illegally maintaining a monopoly, the government first has to prove that the tech giant in question actually has one. In the most famous tech antitrust case, United States vs. Microsoft, the defendant had more than 90 percent market share of operating systems for personal computers

The global smartphone market is more fragmented. Apple has a plurality of market share at 23 percent. Most smartphones in the world run on Android. And so the Department of Justice argues that Apple’s monopoly is in the category of “performance smartphones,” which are more expensive, use premium materials, and have extra components and features, such as NFC chips used for contactless payments.

Of these performance smartphones, the suit says, Apple has 70 percent market share by revenue. And from that market definition, it seeks to make the case that Apple illegally restricts competition and inflates prices.

It’s not clear whether a judge will accept this definition. A federal judge threw out an antitrust case against Meta in 2021 for failing to establish that the company had an illegal monopoly in personal social networking services. (The government refiled it two months later, and the case is ongoing.) It may seem obvious that Meta is the most powerful player in social networks in the United States, but the government had a difficult time defining the relevant markets such that it could credibly accuse the company of having a monopoly.

Similarly, it seems obvious that Apple is the dominant smartphone manufacturer in the United States. But the case is less clear cut than US vs. Microsoft, as Matt Rosoff argued in TechCrunch, and until a judge accepts the relevant market definitions there’s no telling if this lawsuit can actually bring about change.

II. What’s changed already

On two of the five charges against the company, Apple has already moved to address competition concerns.

The first relates to apps that can stream video games over the cloud, such as Xbox Cloud Gaming and GeForce Now. Apps like these let users subscribe to play a variety of games for a single monthly fee; in that sense, they can offer developers a way to make an end run against Apple rules that prevent third-party app stores. They also let users play high-end games on low-end hardware, meaning they don’t have to upgrade their devices as often. Apple said it would allow game streaming apps in the App Store in 2020, but only if developers submitted each individual game within the service for review.

Then this January, in response to pressure from European regulators, Apple said it would allow game streaming apps without those onerous extra requirements. So there’s one Department of Justice complaint resolved. But the point that the DOJ was making here — that Apple blocks apps that would let consumers hang on to their iPhones for longer — still stands.

The second charge Apple has moved to address involves iMessage. Many commentators noted today that the DOJ’s lawsuit marked the first known case of the federal government weighing in on green bubbles — and, more broadly, the way Apple intentionally makes the messaging experience worse for non-Apple customers as a way of discouraging customers from switching to Android. As one Apple executive put it in 2016, according to the lawsuit: “moving iMessage to Android will hurt us more than help us.”

In November, Apple said it would support Rich Communication Services, or RCS, at some point this year. It’s not the same as building an iMessage app for Android. But it is a modern messaging standard that will add typing indicators, read receipts, location sharing, and other features that Android users haven’t been able to enjoy when messaging their friends on iOS. If the RCS standard expands to support end-to-end encryption, a move Apple says it will support, security protections for all smartphone users will improve accordingly.

In the meantime, Apple’s moves to protect iMessage highlight the ways it is willing to worsen the experience for consumers, including around privacy and security, in the name of creating lock-in on its devices.

III. The changes still to come

The lawsuit also accuses Apple of improperly restricting access to the NFC chip in the iPhone, which enables Apple Pay. By limiting use of the chip to its own digital wallet, and collecting a fee for every Apple Pay transaction, the company has been able to extend its dominance, the suit argues.

On this point in Europe, Apple has already thrown in the towel. In January, the company said it would open up its tap-to-pay technology to other companies. And while it will surely fight the broader claims in the DOJ’s lawsuit, when it comes to digital wallets, it’s clear that Apple is ready to make concessions.

That leaves two outstanding claims for Apple to address.

The first concerns smartwatches. For developers seeking to integrate their hardware with iOS, the DOJ argues that Apple has improperly restricted them from letting users respond to messages and notifications from their non-Apple watches. Apple also prevents them from ensuring a persistent connection with iPhones, the case argues. The overall effect, the lawsuit states, is to deny users the chance to use smartwatches with “preferred styling, better user interfaces and services, or better batteries, and it has harmed smartwatch developers by decreasing their ability to innovate and sell products.”

It may seem like a minor point. But the watch example illustrates how Apple is taking its dominance in smartphones and using it to ensure that it makes the best smartwatches as well — not only by building better features, but by preventing competitors from matching them.

Finally, the DOJ accuses Apple of improperly restricting so-called “super apps.” The most famous super app is China’s WeChat, which encompasses a huge range of functions, from social networking to commerce. In China, WeChat’s dominance allows people to switch easily from iPhone to Android and back depending on their preference, because most of their digital life is contained within their WeChat account.

I find this the least compelling aspect of the DOJ’s case, since WeChat is a uniquely Chinese phenomenon. WeChat took off in large part because of heavy regulation from China’s authoritarian government, which blocked competition from western apps. Moreover, WeChat is so dominant in China that if it were similarly successful in the United States, the DOJ would probably be trying to force its divestiture or ban it. (Or, if it were American-owned, break it up for its own anticompetitive behavior.)

If the underlying argument is that Apple should permit third-party app stores, the DOJ should say that. If its argument is that Apple should permit apps that contain within them an unlimited number of other apps, that seems more fraught. The more different experiences an app enables, the harder it is for Apple to evaluate it for security, privacy, and other concerns. Ultimately, I’m not convinced that consumers are harmed by having to download different apps for different purposes. Almost all of the most important apps are available on Android and iOS, and it’s not clear to me that people would be more willing to switch to Android if an American WeChat existed.

IV. What if the DOJ wins?

Antitrust cases face long odds and take years to resolve. By the time this case is decided, it seems quite likely that the most pressing concerns about competition in tech will lie elsewhere.

Moreover, given that Apple has already basically conceded 60 percent of the lawsuit to regulators, it’s fair to ask how much would change even if the government prevails.

But in a world where there is a smartphone duopoly, it matters whether the dominant players open up key APIs and other system features for competition — or hoard them to themselves. It matters whether they enable rivals to build worthy accessories, or place artificial limits on them to ensure that their products are inferior. It matters whether developers of essential apps for messaging, music, and other services can compete on an even playing field, or whether they get kneecapped by App Store economics and self-preferencing.

And while Apple will surely protest this case with every fiber of its being, in the end the company has only itself to blame for the backlash it’s now experiencing around the world. No one can question the excellence of the company’s product line. But the arrogance with which it dismisses efforts to regulate it, and the greed that is evident in the ever-rising cost of iPhone ownership, undercuts that fine work.

For too long now, Apple has defended its anticompetitive behavior as necessary to protect consumers’ security and privacy. But in its lawsuit, the DOJ recognizes this rhetoric for what it is: self-serving and disingenuous.

“Apple selectively compromises privacy and security interests when doing so is in Apple’s own financial interest — such as degrading the security of text messages, offering governments and certain companies the chance to access more private and secure versions of app stores, or accepting billions of dollars each year for choosing Google as its default search engine when more private options are available,” the lawsuit states. “In the end, Apple deploys privacy and security justifications as an elastic shield that can stretch or contract to serve Apple’s financial and business interests.”

Apple will surely continue to deploy that shield throughout the legal battle to come. But the facts laid out in the DOJ’s case against the company show that it has a formidable arsenal of its own. And when all is said and done, the big blue bubble Apple has been living in may burst once and for all.

Join us in New York on April 1 for a Twitter funeral and Extremely Hardcore book party hosted by The Verge! Tickets are $40 and come with drinks and a copy of Zoë's book. Get yours now.

On the podcast this week: Kevin and I break down the DOJ's lawsuit against Apple. Then, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt joins us to make the case that social networks are rewiring teenagers' brains. And finally, on the occasion of Reddit's IPO, we discuss what the site means to the internet.

Apple | Spotify | Stitcher | Amazon | Google | YouTube

Governing

- The House of Representatives passed a data privacy bill that would stop certain companies from selling information to “foreign adversaries." Great, now do one for domestic data brokers. (Alfred Ng / Politico)

- The Senate’s next step in the TikTok bill is most likely to hold a hearing, with no commitments to put the bill on the floor yet. (Ashley Gold / Axios)

- X locked and suspended the accounts of journalists and researchers who shared the alleged identity of neo-Nazi cartoonist Stonetoss. (David Gilbert / WIRED)

- Trump Media’s multi-billion merger with Digital World Acquisition faces mounting legal challenges. (Drew Harwell / Washington Post)

- The FBI has resumed its efforts to share information with tech companies about foreign propagandists on their platforms. Good! (Kevin Collier and Ken Dilanian / NBC News)

- Parler is planning a comeback in the App Store, and now has owners who say it won’t host violent content. (Makena Kelly and William Turton / WIRED)

- The Mozilla Foundation, along with other signatories, released an open letter calling on Meta to keep CrowdTangle functioning until January 2025, at least through the election year. (Mozilla Foundation)

- Texas attorney general Ken Paxton is suing xHamster and Chaturbate, saying that the sites don’t comply with the state’s age verification law. (Samantha Cole / 404 Media)

- Google researchers found a way to use AI to help improve flood forecasting, which can provide accurate information up to seven days in advance. (Yossi Matias / Google)

- The EU Commission is rolling out election disinformation rules that could fine social media platforms insufficient content moderation. (Javier Espinoza / Financial Times)

- Google was fined about $271 million by the French competition authority, for breaking its commitments to license content from media outlets. (Samuel Stolton / Bloomberg)

- India’s IT ministry said it plans to create a fact-checking unit for government-related matters on social media. Bad! (Manish Singh / TechCrunch)

- Apple’s Tim Cook said China's supply chain is “critical” to its business, in a visit to the country. (Ryan McMorrow / Financial Times)

Industry

- Reddit shares soared 48 percent above their IPO price as investors warm up to its AI vision. (Ryan Gould, Amy Or and Katie Roof / Bloomberg)

- Reddit’s IPO, after the company transformed from a toxic mess to a trusted news source, is a victory for content moderation. (Kevin Roose / New York Times)

- Microsoft was able to acquire Inflection AI without actually buying the company, in a novel end run around regulators. (Camilla Hodgson / Financial Times)

- The tech giant reportedly agreed to pay Inflection about $650 million in a licensing deal designed to placate its investors, who were otherwise left with the husk of a company that they just recently put more than $1 billion into. (Jessica E. Lessin, Natasha Mascarenhas and Aaron Holmes / The Information)

- OpenAI is reportedly set to release GPT-5 sometime mid-year. (Kali Hays and Darius Rafieyan / Business Insider)

- Key members of the AI research that developed Stable Diffusion have reportedly resigned from Stability AI. What is happening at this company? (Iain Martin and Kenrick Cai / Forbes)

- Threads is rolling out a fediverse beta in the US, Canada and Japan, letting users cross-post and view likes from other platforms like Mastodon. Given all the skepticism that Threads would ever join the Fediverse, this is really nice to see before the app is even a year old. (Emma Roth / The Verge)

- X will now allow developers to pay for upgrades that fetch about 10,000 posts for $100 if they hit their tier limit midway through the month. (Ivan Mehta / TechCrunch)

- Amazon is reportedly now focusing on Temu and Shein as its main competitors, moving on from past rivalries with Walmart and Target. (Sebastian Herrera / Wall Street Journal)

- YouTube TV is rolling out support for Multiview on iPhone and iPad. Looking forward to watching four videos simultaneously on a phone to destroy what is left of my attention span. (Ben Schoon / 9to5Google)

- Cohere, a startup viewed as a strong OpenAI competitor, reportedly only made $13 million in revenue last year. It's a sign of the challenge AI companies are having in finding product-market fit. (Stephanie Palazzolo and Maria Heeter / The Information)

- Android will be getting an Epic Games Store. (Ben Schoon / 9to5Google)

- The Browser Company has reportedly raised $50 million in a round led by Pace Capital. Big number for a company without a business model and a lot of legal battles in its future. (Ivan Mehta / TechCrunch)

- How eight Google researchers turned neural networks into a digital system and invented modern AI. An in-depth look at the team that invented the transformer. (Steven Levy / WIRED)

- Your data may be shared with more than 1,500 companies when you visit popular websites. (Matt Burgess / WIRED)

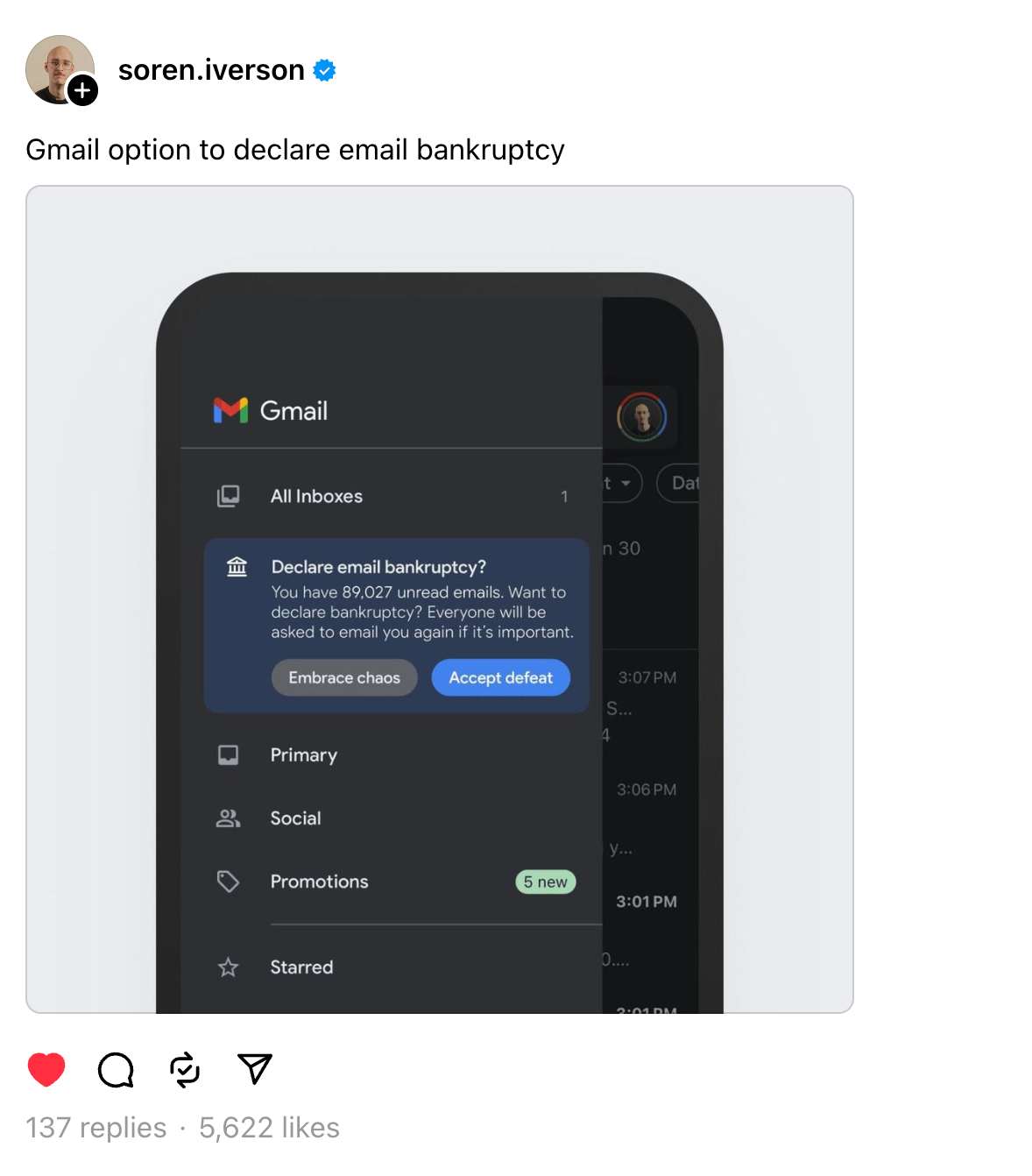

Those good posts

For more good posts every day, follow Casey’s Instagram stories.

(Link)

(Link)

(Link)

Talk to us

Send us tips, comments, questions, and antitrust arguments: casey@platformer.news and zoe@platformer.news.